Sigma Nu Hall of Fame

2023 Inductees

During the 70th Grand Chapter, the Fraternity inducted four brothers into the Sigma Nu Hall of Fame. Established in 1982 at the 50th Grand Chapter in Snowbird, Utah, induction into the Hall of Fame may occur for an alumnus, living or dead, who has distinguished himself in his respective field in a manner to bring great credit to the Fraternity. Sigma Nu Fraternity is proud to announce the induction of the following exceptional Brothers into the Hall of Fame: Businessman and entrepreneur Carl Thoma (Oklahoma State), College Football Hall of Fame coach LaVell Edwards (Utah State), Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame coach Guy Lewis (Houston), and ace World War II pilot and hero Col. Hubert Zemke (Montana). We congratulate Brothers Thoma, Edwards, Lewis, and Zemke on this high honor and extend a hearty Hi Rickety to each brother for their exceptional accomplishments.

Carl D. Thoma (Oklahoma State) - Epsilon Epsilon #1069

Carl D. Thoma (Oklahoma State)

Brother Carl Thoma of Chicago, Illinois, earned his bachelor's degree in agricultural economics from Oklahoma State University in 1970. He received a master's degree in business administration from Stanford's Graduate School of Business in 1973.

As a student, Carl joined the Epsilon Epsilon Chapter at Oklahoma State University in 1967 and was in school with other notable Sigma Nu Brothers and Sigma Nu Hall of Fame members, Don Humphreys, Charlie Eitel, Tom Coburn, and Burns Hargis. Dr. William “Bill” Spears, an earlier initiate of Epsilon Epsilon Chapter, is also a member of the Hall of Fame.

Thoma represented the College of Agricultural Sciences on the Student Senate, was president of the Blue Key Honor Society, and was named to Who's Who. He also served as Lieutenant Commander to the Epsilon Epsilon Chapter.

Thoma began his career in private equity with the First National Bank of Chicago. In 1980, he founded Thoma Bravo, LLC, which has invested more than $40 billion in growing companies over the past 35 years. Fortune, The Wall Street Journal, and Business Week have cited Thoma for his investment leadership.

He is most noted for his success in PageNet, where his firm made more than 100 times its investment and secured numerous cellular licenses that are now a critical part of AT&T's cellular network. Thoma has served as chairman of the National Venture Capital Association and the Illinois Venture Capital Association, on the Boards of Copia, the American Center for Wine, Food, and the Arts, Northwestern Evanston Hospital, and the Illinois Institution of Technology.

Thoma is actively involved on the advisory councils of the Stanford Graduate School of Business and the Illinois and National Venture Capital Associations. He was inducted into the Chicago Area Entrepreneurship Hall of Fame in 1998. The Illinois Venture Capital Association named him the first Stanley C. Golder Award recipient as a leading venture capitalist in Illinois.

Carl also remains involved with Oklahoma State University, serving on the Riata Center for Entrepreneurship advisory board, and has previously served on the Oklahoma Higher Education Regents’ Committee for the evaluation of state colleges.

The Spears School of Business at Oklahoma State University, named after Epsilon Epsilon Chapter Brother Dr. William Spears, inducted him into its Hall of Fame in 1996. In 2002 he received the Oklahoma State University Distinguished Alumni Award.

Carl and his wife, Marilynn, were inducted into the Oklahoma State University Hall of Fame in 2010 and the OSU Greek Hall of Fame in 2020.

Brother Thoma is currently on the boards of the McKnight Center for the Performing Arts, New Mexico School for the Arts, the Phoenix Art Museum, and SITE Santa Fe.

Carl and Marilynn have been supporters of the Arts for many years. They have a world-class art collection which they share with the public. Together he and Marilynn run the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation, a grant-making organization dedicated to sharing its collection and supporting museums, projects, and individuals pursuing innovative ideas in the visual arts.

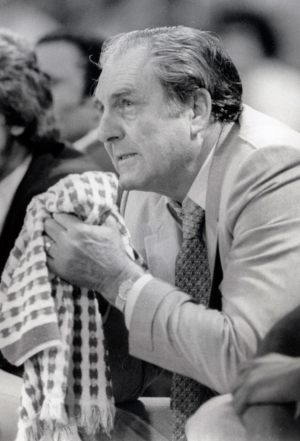

Guy V. Lewis (Houston) - Zeta Chi #464

Guy V. Lewis (Houston)

Guy Lewis enrolled at the University of Houston on the G.I. Bill after serving in World War II. He played center and forward on Houston's first varsity basketball team, graduating in 1947.

Brother Lewis served as the head men's basketball coach at the University of Houston from 1956 to 1986. He was known for plaid jackets and wringing his hands with a red polka-dot towel during games.

Lewis led his Houston Cougars to 27 straight winning seasons, 14 NCAA tournament trips, and five Final Four appearances.

Guy was a major force in the racial integration of college athletics in the South during the 1960s, being one of the first major college coaches in the region to actively recruit Black athletes and was known for championing the once-outlawed dunk.

Lewis's insistence that his teams play an acrobatic, up-tempo brand of basketball that emphasized dunking brought this style of play to the fore and helped popularize it amongst younger players.

His 1980s teams, nicknamed “Phi Slama Jama” for their slam dunks, were runners-up for the national championship in back-to-back seasons in 1983 and 1984.

Brother Lewis was known for putting together the “Game of the Century” at the Astrodome in 1968 between Houston and UCLA. It was the first regular-season game to be broadcast on national television. Houston defeated the Bruins in front of a crowd of more than 52,000, which, at that time, was the largest ever to watch an indoor basketball game.

In 1983, the Cougars suffered a dramatic, last-second loss to underdog North Carolina State in the 1983 NCAA Final that became an iconic moment in the sport’s history, one that solidified the NCAA basketball tournament in the cultural firmament as March Madness.

Standout players Lewis coached during his tenure at Houston included Elvin Hayes, Don Chaney, Otis Birdsong, Dwight Jones, Louis Dunbar, Ken Spain, Akeem Olajuwon, and Clyde Drexler.

In 1995, the University of Houston named the playing surface at Hofheinz Pavilion (now the Fertitta Center) "Guy V. Lewis Court" in Lewis' honor, making him a university namesake.

In 2007 Lewis was inducted into the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame, and in 2013 he was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

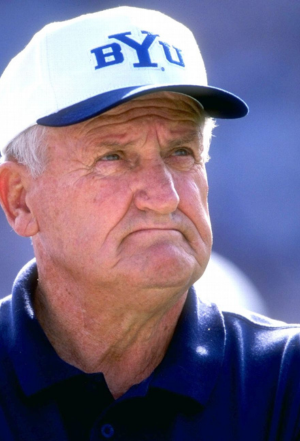

R. LaVell Edwards (Utah State) - Epsilon Upsilon #292

R. LaVell Edwards (Utah State)

Brother Edwards attended Utah State University to play football. He joined Sigma Nu Fraternity in 1949. As a student-athlete, he played center and linebacker and was voted honorable mention All-American his senior year.

Upon graduation, LaVell served in the United States Army in Japan at the end of the Korean War. Upon completing his duty, he fulfilled his lifelong desire to become a football coach.

He was hired as a defensive coach at BYU in 1962 and later became the defensive coordinator. He was named head coach at BYU in 1972. He decided that his defenses would be rugged and hard-hitting, and his offenses would emphasize the forward pass, a novel concept for the time.

Edwards coached BYU for 29 years, from 1972 to 2000. He is tied for seventh in all-time wins among NCAA Division I football coaches. He retired with 257 wins. Under his guidance, BYU won 20 conference championships and went to 22 bowl games.

In 1984, he was named National Coach of the Year for the second time after BYU finished the season 13–0 and won the National Championship.

He has coached numerous All-Americans, four Davey O'Brien trophy winners, two Outland Trophy winners, and a Heisman Trophy winner.

Edwards’ teams were known for their high-flying passing attacks at a time when the running game still dominated college football. His quarterbacks threw over 11,000 passes for more than 100,000 yards and 635 touchdowns.

Edwards coached prominent quarterbacks such as Steve Young, Jim McMahon, Ty Detmer, and Steve Sarkisian.

Before Edwards' final game, BYU renamed its home field, Cougar Stadium, LaVell Edwards Stadium, in his honor.

Brother Edwards finished his career 22nd on the NCAA all-time list for coaching victories. He coached six all-American quarterbacks. His teams led the nation in passing offense eight times, total offense five times, and scoring offense three times.

In 2004, he was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame.

Col. Hubert A. "Hub" Zemke (Montana) - Gamma Phi #339

Col. Hubert A. Zemke (Montana)

Col. Hubert “Hub” Zemke was a pre-eminent World War II fighter commander in the entire European theater. A general once described Col. Zemke as a typical fighter pilot: "chip on his shoulder, makes excellent eye contact, not insolent, just confident." He was an extraordinary man, meeting the challenges of extraordinary times. He was outspoken and courageous, with unwavering personal integrity and conviction.

Hubert Zemke was born and raised in Missoula and became a member of Sigma Nu at the Gamma Phi Chapter at the University of Montana in 1934. After graduation from college and upon advice from friends, Zemke explored the fighter training program of the Army Air Corps.

Immediately he displayed a proficiency that found him assigned to the 36th Fighter Squadron at Langley Field, Virginia. Before long, he was logging 20-30 hours a month testing P-40s at Wright Field and flying in the Cleveland Air Races.

In April of 1941, before the United States entered the war, Zemke transferred to England as a combat observer.

By June, he served as Assistant Military Attaché to the American Embassy in Moscow, where he trained Soviet pilots in British P-40s. The United States had entered the war by February 1942, and Lt. Zemke was anxious to join the fray for the U.S. With war raging in Europe, Zemke had to weave his way through Tehran and Cairo before finally reaching American soil.

Subsequent assignments included the 56th Fighter Group, an inspection tour of 120 Chinese pilots, squadron commander of the 59th fighter group, and by August 1942, reassignment to the 56th. This time he was the commander.

In early 1943, the 56th was transferred to King's Cliffe, England, where Zemke began experimenting with new flight formations. His group, now known as "Zemke's Wolfpack," proved to be a catalyst for numerous organizational and tactical developments. These included creating a combat fighter group, which integrated aircraft maintenance. They also conducted the first planned strafing of an enemy airfield and the first dive-bombing attempt. Their planes carried cameras for aerial photography and extra fuel tanks to boost flight distance for bomber escorts.

The 56th was truly a formidable force. And Zemke was both the catalyst and the momentum behind their success. In May 1943, at age 29, Zemke received a promotion to full Colonel, and he promptly initiated a new combat tactic, the "Zemke Fan." It allowed fighters to roam freely ahead of the bomber formation, preventing the Germans from forming up to attack.

By November 1943, the 56th had produced six aces, including Zemke. He would eventually score 19.5 aerial victories, and the Wolfpack would end the war with 992.5 confirmed kills, more than any other Eighth Air Force fighter group.

As October drew to a close and his combat hours passed 450, Zemke knew his days as a group commander were about to end. He was ordered to the 65th Fighter Wing headquarters as chief of staff. With packed bags, he decided to fly one more mission before taking over a desk.

On that mission, he ran into the worst turbulence he had ever encountered. He ordered his formation to turn back, but before he could do so, his P-51 lost a wing. Parachuting from the wreckage, Zemke was soon taken prisoner and ended up in Stalag Luft I at Barth, Germany, on the Baltic Sea.

Newly arrived, Colonel Zemke found himself a senior officer in command of 7,000 Allied prisoners, some of whom had been there for several years. Conditions were deplorable: insufficient food, inadequate clothing, and medical attention, a lack of military discipline among some POWs, and indifferent or hostile German officials.

Zemke quickly established his leadership of the POWs, who numbered about 9,000 by V-E Day. Gradually he developed working relations with the prison commandant and staff and achieved some improvements in living conditions.

When it became apparent that their war was lost, the Germans became more cooperative, especially as Soviet armies approached from the east. Zemke and his staff negotiated an arrangement with the camp commandant for the Germans to depart quietly at night, bearing only small arms, and turn the camp over to the Allied POW wing.

To avoid conflict between some POWs and the hated guards, Zemke’s staff kept the arrangement secret until the morning after the German departure. Zemke then nurtured friendly relations with the arriving Soviets. (In 1941, he had spent several months in the USSR teaching Russian pilots to fly the P-40. He spoke some Russian and fluent German.) Ultimately, Zemke arranged for the POWs to be flown to Allied territory. His strong leadership saved the lives of many POWs.

As his war-weary men returned to the United States, Zemke remained in Europe, searching for missing American prisoners-of-war and returning them home.

Zemke spent the remainder of his outstanding Air Force career in various leadership roles, including president of the Air Force's Air War College, secretary of NORAD, and Reno Air Defense Sector commander.