Features

When Ray Pavy (Indiana) was in high school in New Castle, Indiana, in the late 1950s, he had much going for him: He was a popular, standout basketball player from a good family, playing in what he said was the best basketball conference in the nation. He was twice named all-sectional and all-regional and was captain of the Indiana All-Star team.

Friday nights during winter were reserved for high school basketball, and everybody who’s anybody was at the game. New Castle home and away games sold out. Even workers on the assembly line at the nearby automobile plants would brag about their team’s win, giving those from neighboring towns a hard time if theirs lost. And, Pavy and his powerhouse team gave them plenty to talk about.

“You play for a while and you realize you were pretty good and that you can help other people [on the court],” says Pavy, deflecting the attention from him while speaking about his shooting skills and his ability to get the ball to a teammate in scoring position.

Those abilities got Pavy a basketball scholarship to his dream school, Indiana University (IU) – something that would have been out of reach without the assistance, as his family was not well-off. Pavy was initiated into Sigma Nu when he got to IU, where he eventually learned just how much his brothers would be his support system. His face lit up as he talked about his passion for the game from his bed at the Edgewater Woods retirement home in Anderson, Indiana, where he was recovering from a bedsore, a common problem for paraplegics.

Pavy reminisced about the days before his accident on Sept. 2, 1961, when the car he was driving collided with a truck on U.S. Highway 52 in northern Indiana. Pavy and his fiancé, Betty Sue Pierce, were on their way to a fraternity brother’s wedding in Whiting, Indiana; they were also taking Pavy’s sister and her three children to Hammond, Indiana. The accident killed Pierce, left one of Pavy’s nephews in critical condition in the hospital and left Pavy paralyzed.

Pavy’s nephew eventually recovered; Pavy’s sister and her other two children escaped serious injury. Pavy, who broke his T4, T5 and T6 vertebrae in his upper back, was in the hospital until Christmastime.

“Of all of the things that drove me nuts was when the doctor came in [to my hospital room] the day of the automobile accident and said, ‘You will never walk again.’ Your mind goes to a low place,” says Pavy.

“That was on the same day that he came in to say, ‘We’re going to operate on your back under local anesthesia,’” Pavy says about what turned out to be an hours-long surgery.

The Making of a Local Hero

While Pavy was in the hospital, Gary Long, (Indiana), and his new bride visited him. The Longs had just gotten married that Labor Day weekend and had been on a short honeymoon. Their rehearsal dinner was the night of the accident, and after the wedding, they took off to southern Indiana. They rushed back when word of Pavy’s accident reached them.

Not only had Long roomed with Pavy in the chapter house during Pavy’s freshmen year, but Long also knew Pierce. The New Castle, Indiana, woman had occasionally asked Long about Pavy before she started dating him; eventually they all went on double dates together.

When Long saw Pavy in the hospital, receiving treatment to stretch his spine, he was shaken. “It was heartbreaking to see him like that,” Long says.

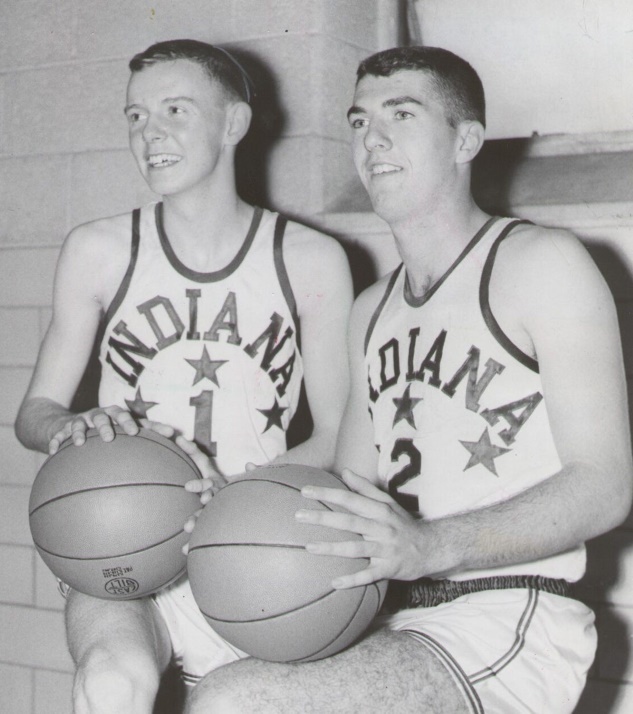

Pavy ultimately took one year off of college; he would have been entering his junior year and a basketball season that promised him more playing time when he was paralyzed. At the time, freshmen could not play varsity basketball at IU, so Pavy and his high school rival, Jimmy Rayl, (Indiana), who was also recruited by the university, had eagerly awaited their sophomore years to play.

“He and Jimmy were the two top guards coming in from high school [in 1959],” Long says of the year they entered IU.

Pavy and Rayl, of Kokomo, Indiana, had played in the infamous “Church Street Shootout” on Feb. 20, 1959, in the 1,800-capacity Church Street Gym in New Castle. It was the last game of the regular season. Pavy and Rayl were making shot after shot in front of a standing-room-only crowd.

It was not until Pavy was fouled and was preparing to take a couple of free-throws that he realized he had scored 49 points.

“Honest to goodness, I did not know how many points I had,” Pavy says from his bed in the retirement center. “One of my teammates [came out] and said, ‘If you make this one, you’ll make 50 [points].’ He was a class clown, so I thought he was joking.”

Pavy made two baskets from the free throw line, ending the game with 51 points. Rayl scored 49 points for Kokomo and went on to take his team to the state championship, where they lost to the Crispus Attucks.

The Church Street Shootout lives in infamy in Indiana, and especially for those from New Castle. This year marked the 60tth anniversary of the much-talked-about game, and reporters were calling Pavy for interviews. He was making headlines once again.

“A lot of people will want to tell me they were there,” says Pavy of the game and the many people who wanted to share in the nostalgia with him.

Pavy played Rayl three times before the Church Street Shootout; they were simply players on opposing teams until they became close friends at IU.

Pavy had come to know about the fraternity through his connections in high school sports. During his time at the university, the chapter was filled with athletes, including Long, who was Commander when he roomed with Pavy. Long was the leading scorer in IU’s highest-scoring game ever, a 122-93 win over Ohio State in February 1959.

When Pavy and Rayl reached their sophomore years, the IU basketball team was already filled with experienced guards, limiting Pavy’s and Rayl’s playing time. The team also included All-American center Walt Bellamy, who was starting center on the 1960 gold-medal-winning US Olympic basketball team. “I was a scorer in high school. [IU] didn’t need another scorer at that time,” says Pavy of his sophomore year.

Instead, Pavy knew what was needed was someone to pass the ball to Bellamy, so he could score, so that is what Pavy set out to do. “If you are on a good team, you learn how to make other people better,” he says of getting the ball into Bellamy’s hands.

Pavy saw playing time that year, but his scoring statistics were not outstanding. However, with Bellamy graduating, he expected to get more time on the court during his junior year.

And then, in September of 1961, the accident happened.

“I’ll never forget where I was when I heard about his accident,” says Butch Joyner, who grew up in New Castle and played IU basketball from 1965 to 1968. “A friend of mine and I were sitting in my living room. We were sitting on a round ottoman watching TV and my mom came in and told me [about the accident.] I was in shock,” says Joyner, who knew Pavy as a star of the Church Street Shootout.

Joyner thinks of what would have been in Pavy’s future had he not have been injured. Not only was Pavy an incredible shooter, but so was Rayl. “They would have been an unbelievable backcourt,” Joyner says.

But, the accident did happen, leaving Pavy with paraplegia and the challenge of adapting to a new normal. He took one year off of college, and then returned to IU. He was greeted by a campus that was not prepared for a student in a wheelchair, but its president, Herman Wells, (Indiana), who did everything in his power to make it adapt for him.

This was long before the Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990, which ensured that public spaces were accessible. Instead, there were steps everywhere, Pavy says. He got around the chapter house because members lifted his wheelchair up and down steps. He had keys to freight elevators across campus so that he could get to some of his classrooms.

Other classrooms changed locations, taking steps out of the equation. “I wanted to be a teacher at four-years-old,” says Pavy. “I wanted to become a [basketball] coach and a teacher.” In order to coach, Pavy was required to study physical education.

“President Wells called my advisor and said, ‘Make sure you get things moved so he can get a phys ed major or minor’,” Pavy says of the classroom switches.

Pavy says moving some of the professors from the rooms they had been in for years frustrated them, but the fact that Wells did it left a lasting impact upon him. He says it taught him to take the extra effort to help someone if you can, even if it irritates others.

It was as Pavy laid in the hospital after his accident that he had begun to realize the need for some of the changes that were made to help him.. “[I thought], ‘How are you going to get around so that you can get places? You know you’re going to have to have help’,” he says. “Had I not have been in a fraternity, I couldn’t have gone back to school.”

His brothers gave him the assistance to get where he needed, and they offered unending support. He says that occasionally he fell into a funk because of the accident. “[But,] when you live with 100 guys, they don’t let you get down very often,” he says.

When he did get down, he says they didn’t mind chewing him out about it.

Pavy graduated in 1965 and taught at Middletown, Indiana, and then at Sulphur Springs, Indiana, where he also coached. He later coached at Shenandoah, a local consolidated school, and though he was successful, that job ended after several years. He had taught for a total of 11 years before he became an assistant superintendent in his hometown of New Castle. He completed his doctorate at Ball State, and as he was doing so, he met and married his wife, Karen.

They have a son, Sam, and a daughter, Dori.

Over the years, Pavy has gone back to IU games, sitting in his wheelchair near the court. And, Long goes down during half-time to visit him. The former college roommates are also regulars at Indiana basketball hall-of-fame functions.

Pavy goes back to his alma mater because he says IU is a family, and of course because he loves the game. It’s a love that has always been there, despite the fact that he had to put up his basketball jersey too soon. From the sidelines in college, he watched Rayl twice be named All-American, receive All-Big Ten honors and be named team MVP in 1962.

Pavy says he wished he could have played, but that it wasn’t hard to watch as he supported Rayl and the team. Rayl was a Cincinnati Royals third-round draft pick in 1963 and went on to play for the Indiana Pacers. He passed away on Jan. 20, 2019.

Pavy says he has lived a good life, in spite of its challenges. For Long, remembrances of the accident remain difficult, and he has thought about how, if he had Pavy in his wedding, Pavy would have been at his wedding rehearsal and not on the road that night. “I always thought about that,” Long says, adding that he knows he cannot blame himself.

Instead, Long shifts to thinking about how Pavy has positively influenced many people. “That might have been what God had in mind,” Long says.

But Pavy says he doesn’t understand why people would call him an inspiration. Others see how he overcame obstacles to live a successful life. He sees himself as a man who simply made the most out of life. “[As] the old saying goes, you pretty much have to play the cards you’re dealt,” Pavy says. “I had basketball talent. I had enough talent to graduate college. All of us would be amazed if we go back and count our blessings. I count my blessings twice.”