Colonel Roosevelt: A Guide for the Modern Man

Bookshelf

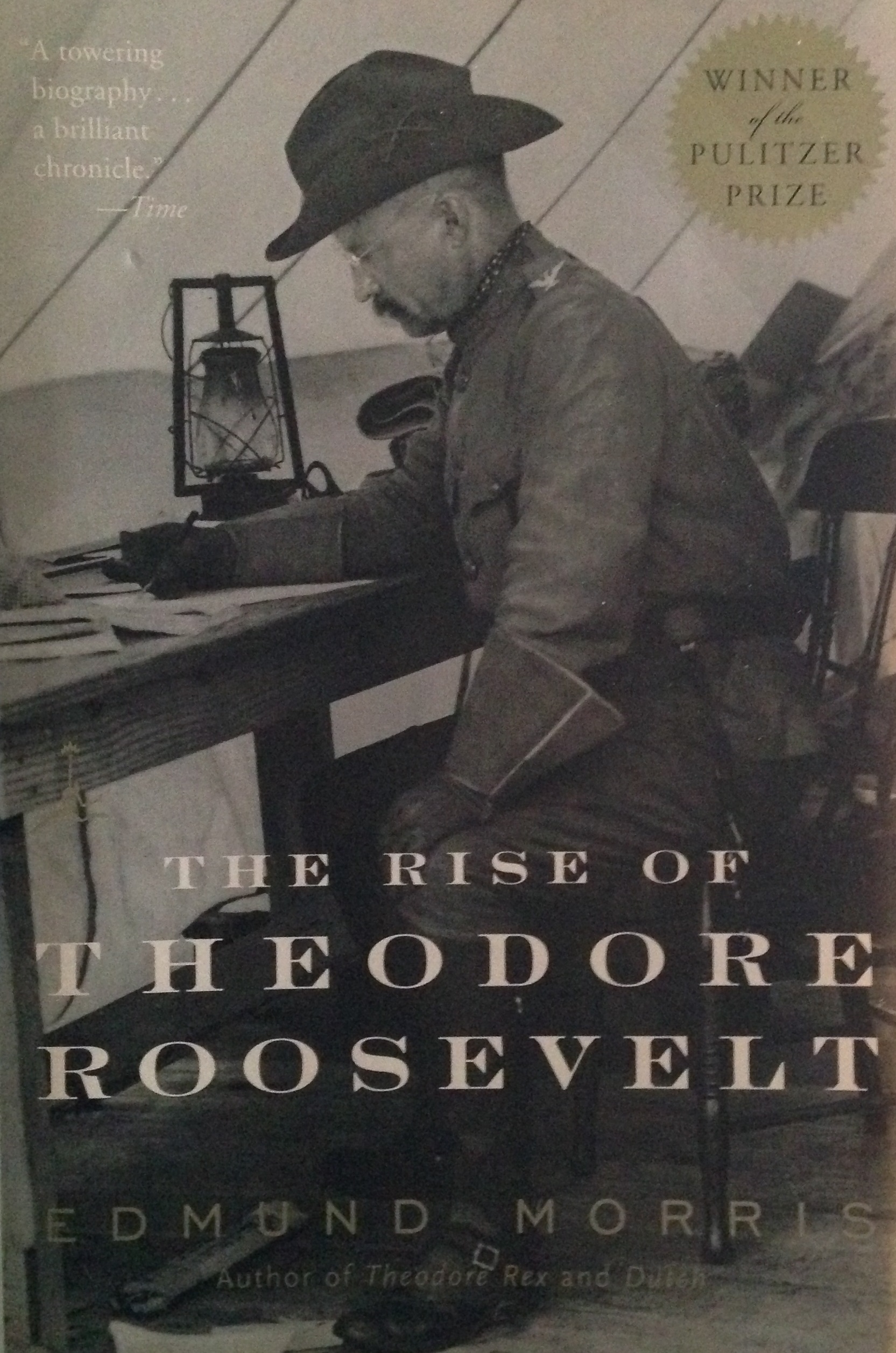

A review of Edmund Morris’ The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt

By Drew Logsdon (Western Kentucky)

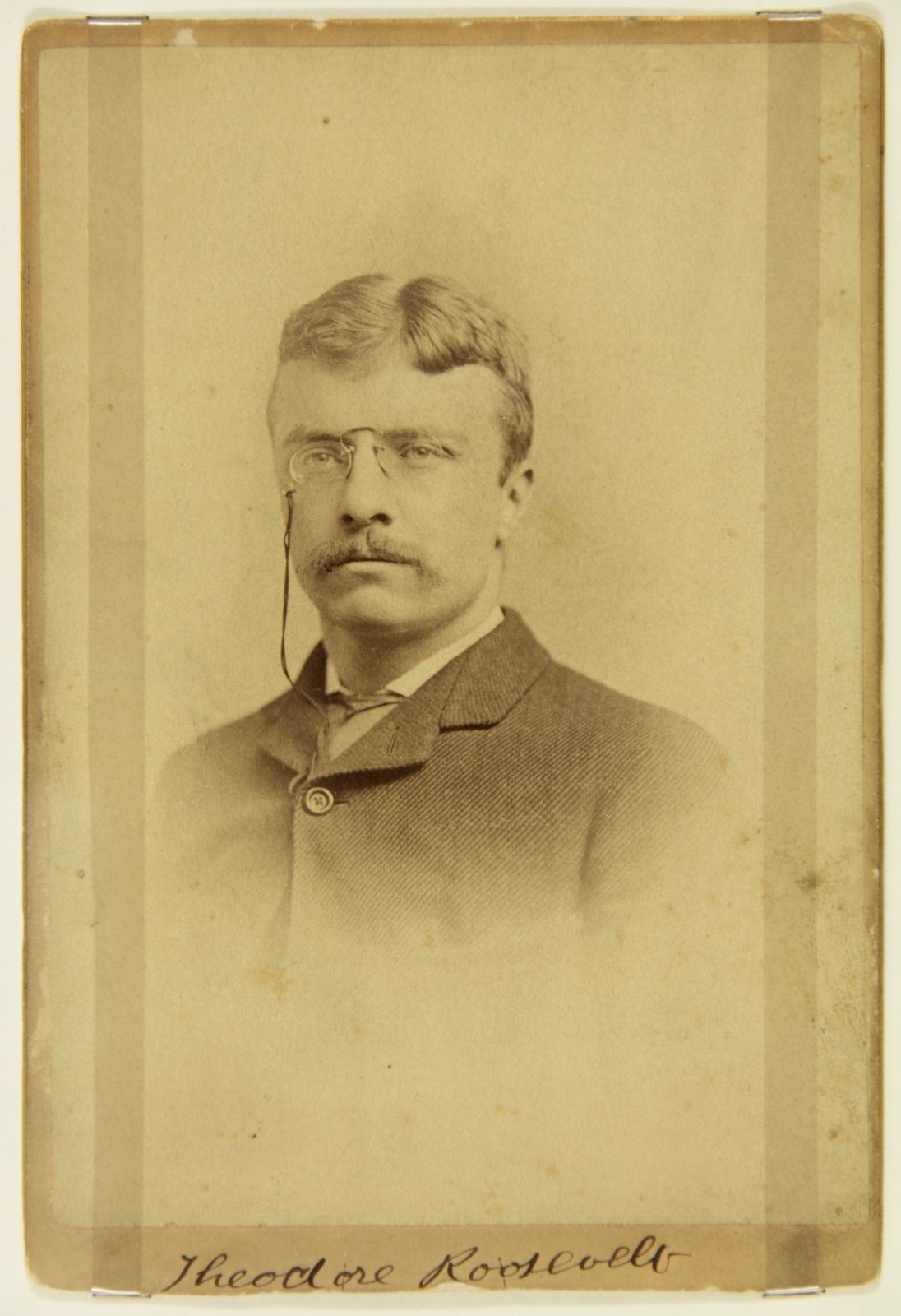

There are few men in American history who have broken so many constraints and categorizations like President Theodore Roosevelt. A quick review of some of his accomplishments illustrates the point. An asthmatic child, he none-the-less devoted himself to such strenuous physical activity as hiking trips to the Italian Alps and boxing lessons to ward off would-be bullies. He became a US Army colonel after serving as assistant secretary of the Navy. A statesman frequently at odds with his own party, he could be boisterous but also delicate and at ease in dealing with kings, barons, counts, and a Kaiser.

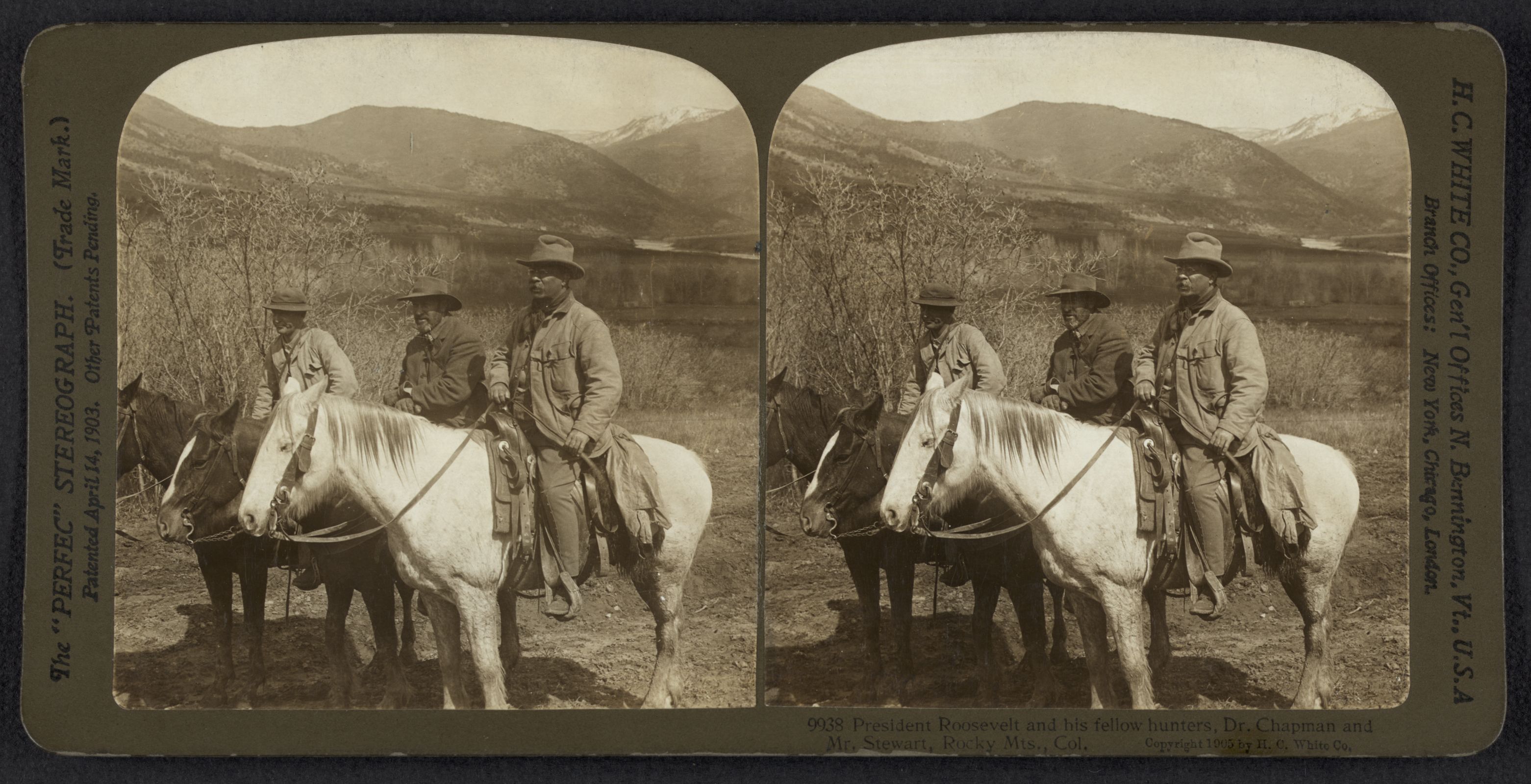

These personal ironies should come as no surprise from the child of a Southern belle and a New York Knickerbocker who came of age during the Civil War. But very few know “Colonel Roosevelt” (as he preferred to be called in his later years) outside of the usual stories. More-so, very few know about his life prior to his Presidency. It is fitting, then, that Edmund Morris had to tackle his biography of Roosevelt in three separate books with the first The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt focusing on his life before the Presidency.

Like any good writer of history, and especially of key figures of history, Morris lets his subject do the talking. In this, Roosevelt does not disappoint. An avid writer, his works included extensive personal correspondence and scholarly books still referenced at the US Naval Academy. He was also a committed diarist (for which we are thankful) and kept very astute records and observations. As the reader grasps the breadth of Roosevelt’s accomplishments and tribulations before his Presidency, it becomes obvious why the biography was best broken into three volumes.

It’s important to realize that Roosevelt was not inherently impetuous, as he is sometimes portrayed. In fact, he moved through life with great deliberation – aside from his personal finances – and took great pains before coming to a decision. His personality had brash qualities but this was not reflected in his deliberations or actions. Even in moments of intense action, he operated within a strict code of conduct and behaved accordingly. Through Morris’ painstaking detail, the reader is privy to the crucible moments of Roosevelt’s early life that would frame his worldview for years to come. For example, his Presidency is well remembered for his conservation efforts that resulted in greatly expanded National Parks and Forests. Morris shows the conservationist’s spirit firmly grounded in Roosevelt’s childhood affinity for natural history where he took great interest in cataloging the natural environment.

Roosevelt’s deeds and accomplishments are meticulously recounted in Morris’ work, so much so, that to attempt to list them all would not be feasible. Let the reader instead draw attention to the great wealth of wisdom we can take from Roosevelt, especially concerning pitfalls of modern manhood.

The Mind and The Body: A Life of Activity

At an early age, Roosevelt’s father told him, “Theodore you have the mind but you have not the body, and without the help of the body the mind cannot go as far as it should. I am giving you the tools, but it is up to you to make your body.” Roosevelt took this counsel to heart and worked hard to stay active, one of his best known qualities. He felt that a keen mind was only fostered by a healthy body and that both should receive regular attention and exercise.

Today this work remains a keystone piece of any naval historian’s library and is standard reading material at the United States Naval Academy.

As a student at Harvard, he began writing The Naval War of 1812 and completed it after graduation. The Naval War of 1812 was received with immediate recognition and no doubt eventually played some part in his appointment as Assistant Secretary of the Navy. Today this work remains a keystone piece of any naval historian’s library and is standard reading material at the United States Naval Academy.

Roosevelt exercised frequently and as a college student in Boston was an avid rower. This activity remained a constant and almost cost him his life when he embarked on a journey through the Amazon rainforest many years later.

“I wish to preach … the doctrine of the strenuous life, the life of toil and effort, of labor and strife,” said Roosevelt addressing the Hamilton Club in Chicago. Indeed, Roosevelt lived what he called a “strenuous life.”

Today, whining has become commonplace over such simple things as slow Internet. Unlike Roosevelt’s doctrine of the strenuous life, modern society has a fondness of idleness in both mind and body. He would no doubt remind us that life is a great adventure and that we have no room for listlessness or allowing boredom to become our best friend.

Values, Love, and Loss

Roosevelt’s college days at Harvard were marked with the enjoyments of a typical college man of those times. He records on at least one occasion being drunk after one of Porcellian Club’s (the finals club he joined in addition to being a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon Fraternity) events.

However, Roosevelt was not someone who chased women. If anything, he negatively viewed those who succumbed to indulgences and thus marred their character and responsibilities. His own brother, Elliott Roosevelt, succumbed to alcoholism at an early age and allegedly fathered a child out of wedlock, which resulted in his exile by the family to a farm in Virginia.

By all accounts Elliott was more academically minded than his brother but was eclipsed by him due to his addiction. Roosevelt called his own brother “flagrant man-swine” and advised that for Elliott’s wife to continue to be with him given his behavior was “little short of criminal.”

Elliott Roosevelt died at the age of 34 from injuries sustained during an attempted suicide. Despite Theodore’s strong disapproval of his brother’s conduct, he was none-the-less deeply moved at Elliott’s death. “Theodore was more overcome than I have ever seen him and cried like a little child for a long time,” wrote one observer.

Loss was not new to Roosevelt. His first wife, Alice Lee Hathaway, died days after the birth of their first child. Hours before, in the same house, Roosevelt’s mother had died from typhoid fever. Years prior, also in the same house, his father died of stomach cancer at the age of 46 while Roosevelt was still a student at Harvard. Following the death of Alice and his mother there is a solitary but poignant note in his diary, “The light has gone out of my life.”

Before reaching a mature age and long before most of his greatest accomplishments, Roosevelt had lost those closest to him. This cascade of tragedies might send a normal man into a tailspin of personal chaos; but, Roosevelt, while grieving deeply, would continue to great personal triumph.

Great men are truly measured not solely by their success but also by the adversity they overcome to reach their accomplishments. Roosevelt is a great example for the modern man to emulate in overcoming intense personal tragedy.

Roosevelt and Fraternity: The Way Forward

Our world and society today are different from when Roosevelt lived. Today we have become enamored with commercialism and the attainment of things to validate who and what we are. Our fraternity system is under near constant criticism. Websites style themselves as humorous and propagate ideas that all fraternity men should be homogenized into buffoonish satires of themselves. They would take no greater delight than the continuation of “man-swine” who have broken their fraternal vows and glorify hazing, misogyny, and ignorance.

For that disease, thankfully Roosevelt’s words from his Nobel Lecture speak across generations for others to listen to and heed. “We despise and abhor the bully, the brawler, the oppressor, whether in private or public life, but we despise no less the coward and the voluptuary. No man is worth calling a man who will not fight rather than submit to infamy or see those that are dear to him suffer wrong. No nation deserves to exist if it permits itself to lose the stern and virile virtues; and this without regard to whether the loss is due to the growth of a heartless and allabsorbing commercialism, to prolonged indulgence in luxury and soft, effortless ease, or to the deification of a warped and twisted sentimentality.”

Roosevelt’s message to the fraternity man of today would no doubt be stern. But, he would also encourage him. “A man’s usefulness depends upon his living up to his ideals in so far as he can,” he wrote to a friend in 1898. His message would undoubtedly be the same to young men of our generation. A firm commitment to the ideals that the fraternity man has pledged himself is the only way to secure a prosperous and honorable life.