Perspectives on Our Past

What is “valor”? It’s a word we’re all familiar with; in fact it’s used in our ritual. The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as “great courage in the face of danger, especially in battle.” In other words, it is the ability to keep moving forward even though the results of your actions could result in your own death.

Fortunately, it’s a situation that most of us will never have to face. We hope we’d react with great courage if ever necessary, but until actually faced with it, we never know for sure.

Many of our brothers, particularly those who have served in the military or as policemen or firemen, have faced those situations. In this column, I’ll talk about two of them; men who exhibited uncommon courage at a time of great danger to themselves and thus will always bear the title – Medal of Honor winner.

The Medal of Honor

Other than those who have served in the armed forces, most of us know very little about the Medal of Honor – why it’s awarded and why its recipients are so revered. The Congressional Medal of Honor is the highest honor that a member of the military can receive.

Although termed “Congressional,” it is now bestowed upon the recipient, or posthumously to his family, by the President of the United States. At the ceremony, it is customary for the President, the Commander-in-Chief of our entire military, to salute the recipient first, rather than vice versa. In addition, forevermore, the recipient when wearing the medal is saluted first by all military men and women no matter what rank they hold

So what does it take to be awarded a Medal of Honor? First of all, it is awarded only to an individual who distinguished himself “conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity” – meaning bravery and fearlessness in an action involving conflict with an enemy. In addition, he must have put his own life on the line and acted “above and beyond the call of duty.” It is this last phrase, “above and beyond the call of duty,” that makes this medal so special. It cannot be awarded to someone for having acted, no matter how heroically, under orders – he must have acted on his own accord and with utter disregard for his own life.

The first Medal of Honor was awarded during the Civil War. At that time, they were awarded more liberally than they are today. To date, over the 150 years they have been awarded, 3,469 have been issued – almost one-half of them during the Civil War. Of the

3,469, just 124 were awarded in World War I out of the 4.7 million men who served.

During World War II, only 464 were awarded out of the over 16.3 million men who served. Many of them have been awarded posthumously. In fact, more than half of the men awarded the Medal since the start of World War II did not survive the action for which they were honored. The medal is not restricted to U.S. citizens and at least 59 Canadians are Medal of Honor recipients.

Sigma Nu is honored to have two of these men among our initiates – Christian Frank Schilt (Rose-Hulman) and Nathan Green Gordon (Arkansas).

Christian Frank Schilt

Christian Schilt was born March 18, 1895 on a farm near Olney in Richland County, Ohio. If ever a man was destined to fly, it was Schilt – unfortunately, planes hadn’t been invented yet. It wouldn’t be until he was eight years old that the Wright brothers flew the first manned flight. However, it’s likely their success caught his attention as a young boy.

Christian Frank Schilt (Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology).

In September 1915, Schilt entered the department of civil engineering at Rose Polytechnic Institute (now Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology) in Terra Haute, Ind. Athletically inclined, he was elected captain of the freshman basketball team. He pledged our Beta Upsilon Chapter that fall and was initiated on February 21, 1916 as badge number 139.

However, his time at Beta Upsilon and Rose was limited because of the entry in April, 1917 of the United States into World War I. Two months later, in June, 1917, he enlisted in the Marine Corps where he continued to serve for the next 40 years rising from buck private to the rank of four-star general.

After enlisting, he went through the same basic training as other recruits, all hoping to join the action in Europe as soon as possible. For Schilt, the Marine Corps decided his talents were better used elsewhere and he was assigned to the first American air unit of any service sent overseas – to the Azores Islands in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. There, his unit, a seaplane squadron, was assigned the task of anti-submarine patrols and he served as a machine gunner on the planes.

His time in the air during these patrols, as well as his exceptional mechanical skills, convinced him that piloting planes would be a lot more interesting than just riding in them. So, at the end of the war, he decided to stick around with the hope of being allowed to attend pilot training. He was accepted and by June 1919, he had earned the designation “aviator,” eligible for “duty involving actual flying in aircraft, including dirigibles, balloons and airplanes.”

A Flying Ace

In Caribbean deployments he honed his skills until he was considered one of the top pilots in the Corps. His timing was fortuitous because the 1920’s were the heyday of air speed races and the armed services participated in them as well – in fact, entry was encouraged. Flying was still very young at the time and few people had experienced it as passengers. Thus, spectators lined up to watch the amazing stunts and speeds of these still relatively new inventions. As plane designs and speeds improved, the public could not get enough of watching them and the men and women who flew them.

Due to his exceptional flying skills, during the period 1923-1927, Schilt flew in most of the national air races and usually was among the top finishers. In 1925, as part of the Pulitzer Race of that year, he finished second to another Sigma Nu, the great Army flyer Lieutenant Earnest Harmon (Bethany). When not racing, Schilt was winning trophies in aerial bombing competitions and serving as a test pilot for new aircraft. Schilt at the time was considered among the top flyers in the country along with Charles Lindbergh, Eddie Rickenbacker and Jimmy Doolittle.

A Hero Emerges

His rendezvous with destiny occurred in 1928 in a small village, with the name Quilali, in the mountain jungles of Nicaragua. In the late 1920’s, Nicaragua, an important strategic Central American country, had recently been engaged in a civil war between the rebel Sandinistas and the government. The U.S. brokered a peace between the warring parties with U.S. Marines serving as guarantors of the peace. However, in 1927 the rebels attacked the Marines and the government forces in bloody engagements throughout the country.

On January 3, 1928, a large force of rebels ambushed a Marine patrol in Quilali. Heavily outnumbering U.S. forces, they pinned the Marines into the tiny mountain village, encircling them in the jungle. There was no escape route and they were running low on food and water. In addition, they sustained heavy casualties that needed medical attention. Staying put meant the troops would eventually be whittled down through well placed shots or starvation. The only way of getting medical attention to the wounded and supplies for the troops was via air.

The Marines sent a signal requesting aerial bombardment of the rebels and a plane to bring supplies and remove the wounded. However, no landing strip was anywhere near the village. With no place to land, it was an almost impossible request. The men, while still under siege and under the cover of darkness, set about building a landing strip on the small dirt road that ran through the village. Over three days they cleared the houses on one side of the street to make it wide enough for a plane – however, it still wasn’t long enough. At one end of the dirt road was the jungle and at the other a sheer drop into the valley below.

To further complicate the situation, the seaplane (O2U-1 Corsair) used by the Marines required modifications to replace the landing pontoons with wheels from a different plane – meaning it wouldn’t have brakes to slow it down on landing. The difficulty of the task would not be made any easier by hostile fire on landings and takeoffs, steep mountains on either side, low-hanging clouds and tricky air currents.

First Lieutenant Christian Schilt volunteered to single-handedly fly the mission.

Due to the lack of brakes and the short landing strip, each landing required Marines on the ground to rush the aircraft and grab the wings to slow it down before it plunged over the cliff. In addition, takeoffs were just as spectacular with four Marines hanging onto the wings while Schilt raced the motor to allow for maximum speed during takeoff to compensate for the short takeoff strip.

Over a three-day period, at the risk of his own life during every flight, he made ten flights into and out of the village under constant enemy fire and almost impossible conditions. Ultimately he evacuated eighteen wounded Marines and delivered 1,400 pounds of food and medical supplies.

A First

In recognition of his heroism, on April 5, 1928, Lieutenant Christian F. Schilt received his Medal of Honor from President Calvin Coolidge at the White House. It was the first time a Medal of Honor recipient was awarded the medal personally by the president at the White House and set the tradition from thenceforth.

Vought 02U-1 Corsair biplane, a scout and observation seaplane.

Brother Schilt would continue to serve in the Marines until his retirement in 1957 – a career of over 40 years. In addition to his service in World War I and Nicaragua, he also served in World War II and the Korean conflict. In addition to the Medal of Honor, he earned 19 more medals over his illustrious career including the Distinguished Service Medal, the Legion of Merit with combat “V” (for heroism), the Distinguished Flying Cross, a Bronze Star with combat “V” and five Air Medals – making him possibly the most decorated Sigma Nu in our history.

Christian Schilt joined the Chapter Eternal at the age of 91 on January 8, 1987.

Nathan Green Gordon

Nathan Gordon was born on September 4, 1916 in Morrilton, Arkansas, the son of a distinguished trial lawyer. After graduation from high school, he attended a community college, Arkansas Poly. A natural athlete, he starred in football (as end) and baseball (at third base) and was named to the all-state team in both sports.

Nathan Green Gordon (Arkansas).

Gordon transferred to the University of Arkansas in the spring of 1936 when offered a football scholarship. He was a key player for the Razorbacks during the 1936 (their first Southwest Conference Championship) and 1937 seasons. On May 7, 1938 he was initiated into the Gamma Upsilon chapter of Sigma Nu at the University. He was elected as their Eminent Commander for the 1938-39 school year. In June 1939 he graduated with a law degree and returned to Morrilton to begin practicing law.

With war clouds rumbling in Europe, Gordon knew it was likely the United States would eventually become involved. In May 1941, slightly more than six months before Pearl Harbor, he enlisted in the Naval Reserve. After initial flight training in Louisiana, he transferred to Florida and in early 1942 was designated a naval aviator. He became a member of the Black Cat Squadron, a group who often flew night missions. Their planes were black and featured a cat’s face with its jaws chomping down on an enemy cargo ship.

Over the next few years, Gordon flew day and night missions in the Caribbean, protecting the Panama Canal. Upon his promotion to squadron patrol plane commander he received orders to the Pacific front. In February 1944, he was assigned to the allied base at New Guinea adding air-sea rescue to their bombing missions. The rescue called for the planes to fly into the target areas during airstrikes, land in the water and pick up downed crewmen.

A Dangerous Rescue Mission

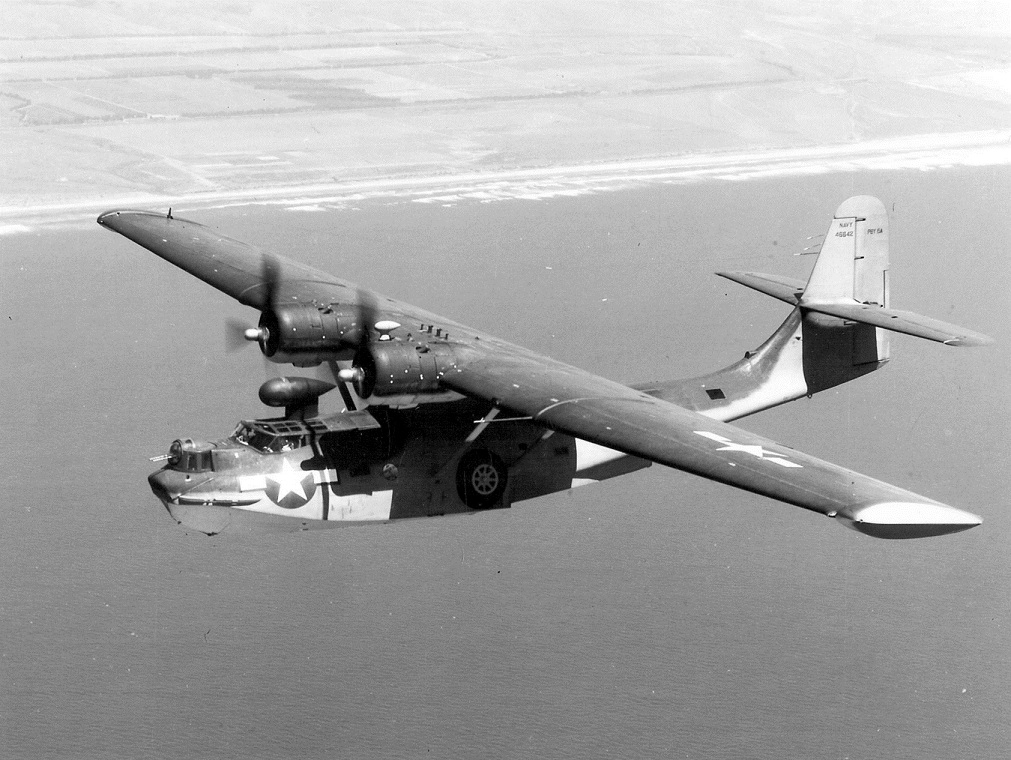

It was on February 15, 1944, during one of these rescue missions that Gordon earned his Medal of Honor with a display of amazing courage. To rescue several downed B-25 bomber crews, he had to fly his plane into the mouth of the heavily-armed Japanese harbor at Kavieng on the island of New Ireland on Papua New Guinea. His plane was a slow and ungainly Catalina seaplane, unaffectionately known as “The Dumbo” or flying elephant. It had a cruising speed of 110 knots, equivalent to an automobile traveling at around 125 mph.

Gordon piloted the plane into the harbor and directly into close range fire from enemy guns. To make matters worse, there were heavy swells in the harbor and almost no wind. To rescue the men, he had to position the plane to land correctly among the 18 foot swells to keep it from breaking apart.

Flying low over the harbor, the crew frantically searched for signs of the wreckage and the downed men. Finally they spotted a partially submerged life raft, but saw no survivors. Knowing that men in the water are often hard to spot from a moving plane, Gordon decided he had to land near the raft to be sure. They dropped smoke bombs near the raft and circled around to land. However, on the approach, he didn’t see the raft in time and had to drop the plane suddenly from too high an altitude. The resulting hard landing caused several of the plane’s rivets to pop and the plane to start taking on water. After taxiing to the raft and further searching it was clear the raft had been strafed and there were no survivors.

Called on Again

No sooner had the plane taken off and started towards home than Gordon received a message from one of his escort fighters about another downed plane. After returning to the harbor and following the directions of the escort pilot, the crew spotted six men frantically waving from a life raft. Gordon made another landing and his crew tossed a line to the raft. While taxiing, he attempted to pull the raft onto the plane. Despite maintaining the Catalina at its lowest idling speed, it was impossible for the crew to pull the raft and its men aboard.

At that point Gordon, as pilot of the plane, had to make a risky decision. He could turn off both engines to stop the plane and rescue the men at the risk of the engines not restarting when the time came to take off (at the time, a not infrequent occurrence). If the engines refused to restart the plane would be a sitting duck for the Japanese artillery. Believing it was the only decision he could make to save the men, he cut the engines, the plane stopped and the men, some badly injured, were pulled safely aboard. We can only imagine his relief when he flipped the switch and the engines restarted.

Taking off for the second time under heavy enemy fire, the plane traveled no more than 20 miles towards home when Gordon received a third message about a downed bomber crew. Upon returning, the crew spotted three men in a life raft and Gordon made another landing into the swells. Again he had to cut the engines to pull the men aboard. After rescuing the men Gordon had an additional concern. The nine rescued men, and his own crew of nine men, severely overloaded the plane and might make it impossible to take off, leading to almost certain death for all of them. Fortunately the engines restarted again and Gordon gave it full throttle. After what must have seemed like an eternity, the plane slowly lifted off above the waves and harbor defenses and once more headed toward home base with cheers from every man aboard.

Uncommon Courage

However, once again Gordon’s valor was severely tested. For the fourth time on a single mission he got a radio call about six more downed airmen. Knowing that his plane was severely overloaded and that he had already rescued nine men, should he turn around and risk it all to try and save the additional six men from an almost certain death. Certainly no one would have faulted him at that point for continuing towards the safety of his home base.

While none of us know what went through his mind, he fearlessly turned the plane and headed once again straight into the jaws of death. There was just no way he could leave the six men behind to the “mercy” of the Japanese troops. This time the men were only 600 yards offshore, virtually under the very nose of the Japanese guns. To position himself correctly for landing, Gordon had to fly directly over the town and the Japanese antiaircraft guns. How he managed without a fatal hit is one of those miracles of war.

Consolidated Catalina patrol boat — unaffectionately known as “The Dumbo.”

For the fourth time, under heavy artillery fire, he landed his plane in the harbor and for the third time turned off his engines. The six men scrambled aboard, shouting their gratitude, but it’s doubtful Gordon even heard them – he had larger concerns at that point. Would the engines restart for the third time and would the plane take off with the extra passengers aboard – 24 men on a plane designed for a crew of nine?

He flipped the switch to start the engines and likely held his breath. Fate once again smiled on Gordon and the men and the engines came to life. Under continuing fire, the plane slowly began taxiing and finally rose a few feet above the waves but could get no higher. Finally, groaning under the weight of its load, it started to climb and Gordon must have breathed a sigh of relief as they finally headed towards home.

For his rescue of the 15 men and remarkable heroism, his superiors cited him for “exceptional daring, personal valor and incomparable airmanship under most perilous conditions.” His entire crew was given Silver Stars and he was awarded the Medal of Honor from a grateful nation.

After the war, Gordon returned to his hometown to once again practice law. In 1946 he ran for lieutenant governor of Arkansas and he won election to a two-year term. He was reelected to that position by the voters nine more times and finally retired in 1967. He still holds the record as the longest serving lieutenant governor in Arkansas’s history.

On September 8, 2008 at the age of 92, Gordon passed away. For initiates in the Legion of Honor, he left a legacy of unforgettable bravery and courage.

Honoring Our Fallen Heroes

These two men showed valor “above and beyond the call of duty.” Although I’ve highlighted Sigma Nu’s two Medal of Honor winners, many of our initiates over the past 145 years have stepped up when called upon to defend our liberties. Some have even paid the ultimate sacrifice with their lives.

We plan to remember and honor these men who gave their lives by enshrining their names forever on the walls of the Memorial Flag Pavilion at the Rock in Lexington. The Flag Pavilion was originally established to serve as a tribute to honor all American and Canadian Sigma Nu servicemen who’ve done so much for so many. It will be enlarged to provide the space for these memorial plaques for those who fell.

The Memorial Flag Pavilion at The Rock in Lexington, Va.

To accomplish this task, we need your help in identifying brothers who died in the many conflicts fought by the United States and Canada. Some were listed in The Delta, mostly from World Wars I and II, but we want as complete a list as we can put together. Perhaps there is a plaque hanging on the chapter room wall or you may have known someone who died. In any case, let us know so we ensure they are appropriately honored and remembered. You can send the names and chapter tonews@sigmanu.org. Additionally, if you are interested in getting involved with this project, please let us know at the same email address.

In a future edition of The Delta, we will publish all the names by individual chapter. Please help us with this important mission to identify and honor those who fell on our behalf.