World War One Centennial and Sigma Nu

History of The Delta

April 6th, 2017 marked one hundred years since President Woodrow Wilson made his plea to Congress for a Declaration of War against the German Empire, thus inserting the United States into a conflict of catastrophic proportions. The sheer scale of fighting, combined with the brutality that comes when invention and the tools of war meet, would eventually lead some to call it the war to end all wars. That phrase would unfortunately not stand the test of time. In honor of this occasion we have dug back into our archives to provide our readership with a letter from a brother during his training camp experience as he adjusts to a new pace of life as a Knight of the Republic and stands on the threshold of history looking towards France. This letter is reproduced here in its original state from the October 1917 issue of The Delta (Volume 35, Number 1) with only the addition of our usual notation of the college/university when a chapter designation is mentioned.

A Training Camp From The Inside

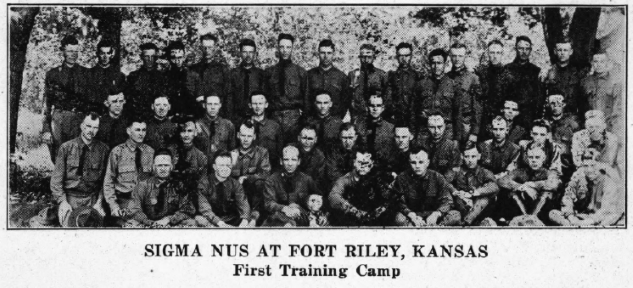

Training Camp at Ft. Riley, Kan.

The first impression on arriving at Ft. Riley was amazement at the size of the fort and the comfort of the quarters provided for our use, for few of us, if any, had heard of the fort before May 1. The reservation itself comprises twenty-two thousand acres of the hilliest land in Kansas, while the post is nothing more than a small, well-paved, well-regulated town. As we got off the train the first thing we saw was one of the cavalry riding halls, a beautiful building of gray stone, typical of the rest of the post buildings. We were met at the station by some of the men who had preceded us, and taken to the administration building, where we were assigned to our respective companies. From here we were taken to our quarters, about a mile away. Here we were issued bedding, and cots, and proceeded to make ourselves at home, and at ten that night, at the sounding of taps, turned in to sleep. That is, our intention was to sleep, but we had few blankets and it was so cold that only one used to an arctic climate could have slept.

The next morning at five a.m. a tired and sleepy bunch turned out for our first assembly, but were soon awakened and livened up by a good, stiff dose of double time. That day and every day for the following week was spent in learning to drill. It was “squads right,” “squads left,” “fall in,” “fall out,” all day long, and beside the physical work, we had lectures and study hours one after the other, and woe betide the man who did not know his lesson. Then, just as were getting settled down, it started to rain, and rained steadily for a week, converting the parade and drill grounds into one mass of mud, locally known as “hog wallow.” But every one, although growling as hard as he could about the conditions, took them good naturedly, for all were so interested in the work that a little mud could never stop them.

At the end of the first month the break-up came. That is, all were assigned to their respective branches of the service. Of course, this necessitated the changing of companies and many of us were lucky enough to be transferred from the modern barracks to stone barracks. The latter are big two-story stone buildings, with the mess halls, and company offices on the lower floor, and the squad rooms on the second, each building capable of housing one hundred and eighty men. Of the temporary wooden barracks the less said the better.

And then the real work started. First we would have a period of drill, and then a lecture, and then a sham battle or problem, while the temperature steadily mounted from one hundred degrees to one hundred sixteen. The worst of it was that one had to keep up with the procession no matter how tired and hot he might be, for, though things came fast and furious, they were never repeated. The time seemed to fly and before one could realize that the week was over, inspection day was on us again. Then we would polish our rifle, a two-hours’ task, shine our equipment, and clean our clothes, for every article we possessed had to be scrupulously clean for the inspection. After the inspection, which took place on the parade ground at eight a.m. every Saturday, we were free for the week-end, according to the schedule. But somehow the schedule was seldom followed and we were given work for Saturday afternoon and lesson to study Sunday.

But at last the end could be seen. The last three weeks were spent constructing model trenches, attacking trenches with bayonet and grenades, just as they are attacked in the present war in Europe, and in field maneuvers.

Of course, many dropped by the wayside, some because of physical defects that the strenuous work developed, some because of lack of adaptability, and a very few voluntarily. But these should in no sense be looked down upon, for not every one is adapted to the work, and it was circumstances beyond their control that caused their discharge.

And now those of us who have been retained and commissioned are to help train the troops that are to win the great war. We have only started to learn and if we are to do ourselves justice and justify the confidence placed in us, we must re-double our efforts. Too much credit can not be given to our instructors, and there is not one of us who would not gladly go as a private, if we could only have “our captain” lead us. And it is the spirit of fidelity and loyalty that we must inculcate in the men we are to lead, and if we can do this, then indeed have we passed the test, and our efforts have not been in vain.

Harry Ambler, Gamma Xi (Missouri S&T)

O.R.T.C., Ft. Riley, Kan., August 1, 1917