Why Do Good People Make Bad Decisions?

Features

By Nathaniel Clarkson (James Madison) and Wendy Lovell

Editor's Note: This feature story was originally published in the Fall 2010 issue of The Delta. It is being republished here in its entirety with only images being edited.

“Evil is knowing better but doing worse.” – Irving Sarnoff

Their pledge semester began in an off-campus houses. Upon arrival, many of the new candidates had 40 oz malt liquor bottles duct taped to both hands; others took shots or bonged beers throughout the evening. An onlooker might have concluded that the goal of Bid Night was to make each new candidate get sick in front of his peers. But Bid Night also succeeded in setting the precedent for what would become a semester of arbitrary and potentially dangerous tasks, culminating with Initiation Week—the preferred euphemism for the week of undesirable activities leading up to initiation.

Thankfully, this story doesn’t end in tragedy, though it very well could have. That a fraternity chapter adopted these negative traditions in the first place should be alarming by itself. But the most alarming, some might say puzzling, piece of this scenario emerges after examining the background of the individual members.

The members of this chapter came from strong families and graduated with honors from the best high schools. They boasted past presidents of the Student Government Association and the Interfraternity Council. They maintained manpower well above the national average and consistently ranked in the top three in grades among all fraternities. They even held a weekly chapter Bible study. The chapter was regarded by most as a paragon of true fraternity.

This story is not just about Sigma Nu’s imperative to eliminate hazing and prevent the misuse of alcohol. Here, we examine the process by which groups of good people can make bad decisions and explore ways to avoid this collective lapse in judgment.

Before proceeding we should make clear that seeking to understand why groups of good men make bad decisions is not a dismissal of personal responsibility. We can hold members accountable while acknowledging that situations matter. We must also recognize that a breakdown in rational group decision-making is not limited to the college fraternity; rather, this phenomenon plagues groups everywhere, from corporate boards to church leaders.

The Lucifer Effect

In his New York Times Bestseller “Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil,” author and psychologist Philip Zimbardo discusses how otherwise good people can commit harmful acts when confronted with powerful situational forces.

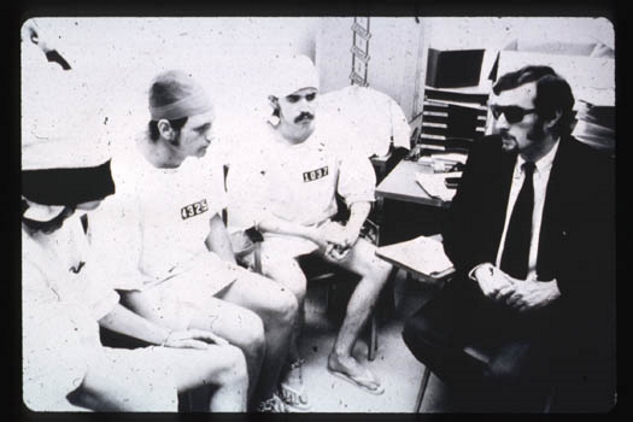

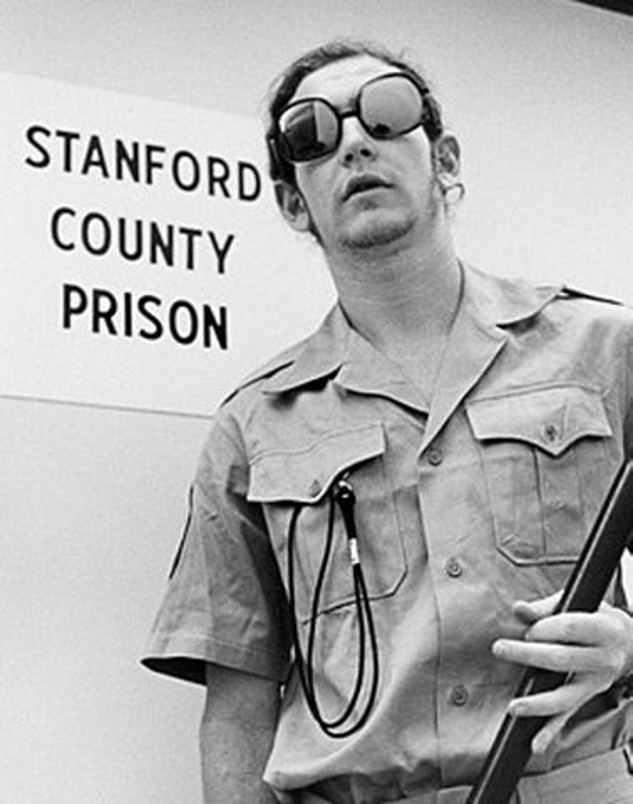

Participants in the Stanford Prison Experiment were randomly assigned to play prisoner or guard in a mock prison. Dr. Zimbardo had to end the experiment early when the guards' behavior became dangerously abusive.

To illustrate his hypothesis, Zimbardo examines several well-known cases of atrocities and other acts of dehumanization such as the Peoples Temple mass suicide and the Rwandan genocide. (To be clear, the purpose of our story is not to equate hazing with genocide but, rather, to identify the process of irrational decision- making caused by situational forces.) Possibly the most compelling evidence of this phenomenon is Zimbardo’s own landmark study, the Stanford Prison Experiment, conducted in 1971.

Zimbardo selected twenty-four college students and randomly assigned them to play the roles of either guard or prisoner while living in a mock prison in the basement of the Stanford psychology building for two weeks. Guards were instructed to preserve law and order in the jail and prisoners were expected to follows the guards’ orders. While the guards were told to prevent escapes, violence against the prisoners was prohibited. The guards became so intensely sadistic and the prisoners so submissive that the experiment was cut short after only six days out of concern for the safety and well-being of everyone involved.

The primary finding of the Stanford Prison Experiment is that the environment created by a group’s culture can have a significant impact on individual behavior. Some situations can exert such powerful influence over individuals that they can be led to behave in ways they normally would not believe possible. While many are quick to blame a group’s behavior on a few bad apples, Zimbardo asks us to consider the possibility of a rotten barrel.

Identifying Causes of the Character Transformation Process

Recall that participants with no prior behavioral problem or authoritarian bent were randomly assigned to the role of guard or prisoner. How did situational forces override these participants with otherwise good dispositions? What process did Zimbardo discover that explains why the guards became sadistic and the prisoners submissive? What were the environmental and cultural factors that fueled this process?

Zimbardo identifies the participants’ exposure to a new environment as the most influential factor in their rapid character transformations. “Situational power is most salient in novel settings, those in which people cannot call on previous guidelines for the new behavioral options,” he says. While stronger chapters tend to recruit men with proven leadership skills, fraternity is a new experience in peer-accountability and self-governance for most joiners.

Experiment organizers also observed that participants, both guards and prisoners, acted out their roles based on stereotypes and other preconceived paradigms. “When actors enact a fictional character, they often have to take on roles that are dissimilar to their sense of personal identity. They learn to talk, walk, eat and even to think and to feel as demanded by the role they are performing.” This observation might explain why a respectful, church-going Brother could become an authoritarian figure when placed in charge of the Candidate education program. The otherwise good Brother is merely acting out what he thinks his role is supposed to be.

Dr. Zimbardo concluded from his landmark Stanford Prison Experiment that good people can commit evil acts when confronted with powerful situational forces.

Zimbardo noted that arbitrary harassment of the prisoners was more likely during the night shift. He suspected that this process of deindividuation was also facilitated when guards wore mirrored sunglasses and the prisoners’ names were replaced with ID numbers. “A body of research documents the excesses to which deindividuation facilitates violence, vandalism and stealing in adults as in children—when the situation supports such antisocial actions.” It’s no surprise that pernicious hazing often takes place in dark rooms where hazers are not easily recognized. (Perhaps this also explains also why vitriolic comments are more likely on the web rather than in person).

Finally, the power of social approval cannot be overstated. The more authoritarian guards pressured the relatively compassionate guards to be “team players.” Similarly, submissive prisoners pressured dissidents to “stop causing trouble for everyone.” The desire to be accepted into the fraternity can be so strong that candidates and brothers will go to great lengths to explain away behavior that is dissonant with the founding principles or even their own, personal values.

When The Lucifer Effect Meets Fraternity

Chad Ellsworth, coordinator of the Office for Fraternity and Sorority Life at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities and president-elect of HazingPrevention.org, has studied Zimbardo’s research as part of his graduate work, and he thinks it has direct application to the arenas of student affairs and Greek life.

“The Stanford Prison Experiment demonstrated that situations matter, and that the line between good and evil is more pliable than we may realize,” he said. “It is possible for social settings to exert a significant impact on the behavior and mental functioning of individuals and groups.”

Ellsworth added that a destructive culture can compel some group members to become bystanders; to remain silent although they know what is happening is wrong and may even strongly disapprove of it. Yet powerful cultural forces stop them from speaking out. Ellsworth says that changing such a culture is challenging but the most effective means is when bystanders decide to speak out.

“Whether the students I counsel have been involved in hazing or other negative behavior, I try to have an honest conversation with them about their values,” said Ellsworth. “If you are aware of your values and know what you stand for, you won’t regret your actions. If you stand for nothing, you can fall for anything.”

Ellsworth works with the Executive Director of HazingPrevention.org, Tracy Maxwell, to raise awareness of the dangers of hazing, encouraging bystanders to speak out and finding ways to generate more research on a problem that plagues many student organizations and teams at most high school and college campuses.

The anonymous Tiananmen Square "Tank Man" has become a universal symbol of courage and heroism. "For reasons we do not yet fully understand, thousands of ordinary people in every country around the world, when they are placed in special circumstances, make the decision to act heroically," Zimbardo remarks.

“Students justify hazing to me all the time,” said Maxwell. “In the context of organizational structure, they are part of a culture of acceptance. We need to recognize the cultural impact this behavior has on students who are young, learning and are under stress.” This cultural impact is just what Phillip Zimbardo studies in seeking to understand why good people commit harmful acts. Nearly every Greek Life professional serves as a witness to the effects, both positive and negative, group culture can have on college students.

Noah Borton (Southern Utah) is Greek Life Coordinator at Eastern Michigan University. Prior to his current job, Noah worked for Sigma Nu General Fraternity as a Leadership Consultant and now serves as a volunteer for the Fraternity. Noah facilitates leadership institutes and helped redesign Sigma Nu’s Pursuit of Excellence Program. He often sees “groupthink” creep into situations with the students he advises. Noah’s comments are reflective of Dr. Zimbardo’s findings during the Stanford Prison Experiment: subjects will adopt the perceived characteristics of the role to which they have been assigned.

“The students aren’t bad people in and of themselves, but in a group, they are led easily,” he said. “Sometimes students have a false idea of what college is supposed to be about; they think they are supposed to have wild times. Ultimately what they want is to be accepted and to have friends.” Borton added that a chapter that establishes its experiences in its values eliminates bad decision-making, whether that behavior is hazing, underage drinking, cheating, discrimination or other risk-taking actions.

Fraternity as the Remedy

“[Truth is the] ceaseless yearning of all men for a wider outlook and nobler existence exemplified in college by a studious search for the means to open wide Life’s windows to the revelations of heaven and earth.” - The Creed of Sigma Nu

In an abstract sense, Sigma Nu’s founding principle of Truth is one remedy to irrational decision-making. In common usage “truth” is often synonymous with honesty, an equally important virtue to be sure. In the context of Sigma Nu’s founding, however, Truth is more closely associated with seeking sound information to make the most informed decisions possible. It calls for the willingness to abandon a false paradigm even if it might be psychologically painful. Seeking the Truth encompasses the process by which we make good decisions. In other words, Truth in practice eliminates The Lucifer Effect. But how exactly do we put Truth into practice to overcome our cognitive blindspots?

On a tangible level, Sigma Nu’s LEAD program puts into practice our founding principles – the very principles that can eliminate the human tendency toward breakdowns in group decision-making. In Phase I, Session 6 (Values), new candidates discuss the meaning of Love, Truth and Honor and how it relates to their personal values. Participants individually study program material in preparation for an interactive discussion with their peers.

The program’s interactive content has received high praise from participants. “I like how LEAD challenges people to think and evaluate the status quo,” said one participant in a recent survey. “LEAD brings the Brothers together and teaches the values of Sigma Nu.”

In addition to implementing our own programs to foster sound decision-making, Sigma Nu joins other Greek organizations in supporting initiatives to eliminate hazing, overconsumption of alcohol and other misconduct that distracts us from our mission to prepare ethical leaders for society. The recent ResponseAbility project is one such initiative. Sigma Nu is a principal sponsor of the program (see ”Sigma Nu Basis For Brother’s Work in Life).

Started by Sigma Nu Brother Mike Dilbeck (Texas Christian), ResponseAbility aims to educate students about bystander behavior—a phenomenon closely related to The Lucifer Effect. “You could say that every problem in the fraternity/sorority community has bystanders,” said Dilbeck. “Something happens—or is happening—and someone sees it, hears about it, or at least knows about it, and does nothing.”

Dilbeck learned about bystander behavior from Dr. Alan Berkowitz, a recognized expert on the social norms approach and bystander issues. His research on why individuals do not intervene has identified four stages in the process of moving from inaction to action. The first step is to notice the event; the second, to interpret the event as a problem; the third to determine whether or not you are responsible for dealing with the problem; and the fourth is to determine whether or not you have the skills and resources to act.

“We all are bystanders because we’re human beings,” said Dilbeck. “The challenge is to practice action, and with practice, we can eliminate a lot of this behavior.”

Sigma Nu is also a partner with HazingPrevention.org which sponsors National Hazing Prevention Week every September and recognizes those who refuse to be bystanders to hazing with the Anti-Hazing Hero Award. The intent of the award is to commend those who have stood up against hazing and to encourage others to do so.

In 2008, Bill Gibson of Gamma Phi Chapter (Montana) was honored by HazingPrevention.org as one of its Anti-Hazing Heroes for his courage in helping put an end to hazing at his chapter. After his election to Commander, Gibson called upon the resources of the General Fraternity to help make a difference in his chapter. Gibson and his Lieutenant Commander had attended College of Chapters and discussed the issues his chapter was facing with a staff member; he was counseled on ways to establish a positive candidate education program.

“I lost a lot of friends and faced opposition from some alumni by forcing the issue, but I did what I thought was right,” said Gibson. “I learned a lot about Sigma Nu at College of Chapters and as an intern at headquarters in 2008; I learned you have to stick with your convictions.”

HazingPrevention.org’s Anti-Hazing Hero Award fits closely with what Philip Zimbardo calls the “everyday hero.” Zimbardo concludes his book with a discussion of heroes:

“By now I hope you are willing to accept the premise that ordinary people, even good ones, can be seduced, recruited, initiated into behaving in evil ways under the sway of powerful systematic and situational forces. If so, are you also ready to endorse the reverse premise: that any of us is a potential hero waiting for a situation to arise that will enable us to show that we have “the right stuff”?”

Encouraging the Everyday Hero

Zimbardo sees great opportunity for people to become everyday heroes by choosing kindness over cruelty, caring over indifference and heroism over evil actions. He believes the keys to resisting the impact of undesirable social influences is self-awareness, situational sensitivity and street smarts. Individuals who can admit mistakes, take responsibility for their actions, maintain a sense of identity and respect just authority are likely to avoid negative situations.

Zimbardo asks readers to consider different types of heroes, distinguishing between “physical-risk heroes” and “social-risk heroes.”

“Less dramatic forms of heroism occur when an individual confronts a system with news it does not want to hear,” says Zimbardo. He references several real life examples of everyday heroes including those who courageously exposed the widespread corporate fraud at Enron and WorldCom.

“For reasons we do not yet fully understand, thousands of ordinary people in every country around the world, when they are placed in special circumstances, make the decision to act heroically,” he concludes.

Likewise, The Legion of Honor calls upon each initiate to act heroically every day by governing each act by a high sense of honor. This is the Sigma Nu antidote to both groupthink and the “Lucifer Effect.”

“All that is required for evil to prevail is for good men to do nothing.” - Edmund Burke