Honoring the Great War

Features

By Drew Logsdon (Western Kentucky)

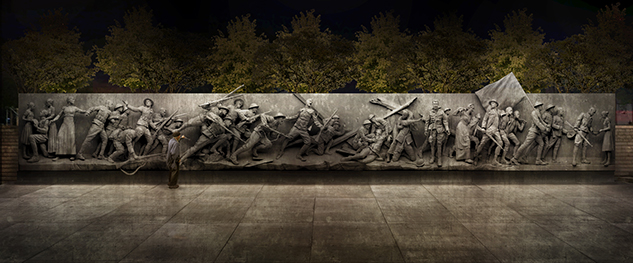

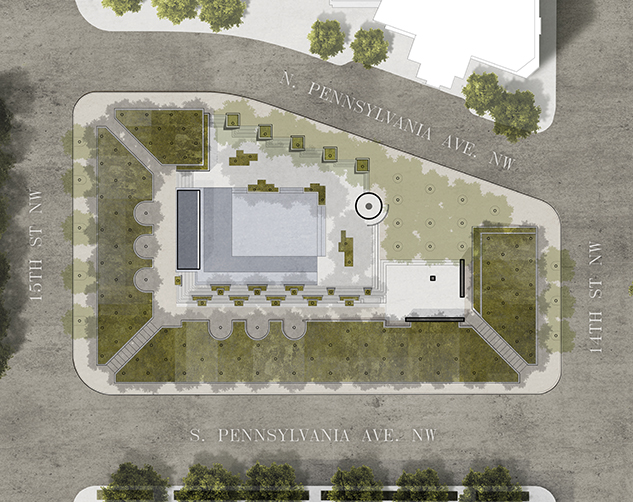

An artist's rendering of the World War One Memorial design in Washington, D.C.

World War I’s impact on the world, and American society in particular, is fading from our collective memory but Dale Archer (Central Oklahoma) is working to ensure we never forget the sacrifices made or the legacy the “war to end all wars” left behind.

100 Years ago, in a train car in the woods of France, the Armistice of 1918 was signed between the Allies and the German Empire, putting an end to all land, sea, and air combat across Europe. This agreement effectively ended World War I, but the tremors of that great conflict have rippled across the world and left no society untouched from its influences and aftermath. In Great Britain, an entire generation of men had been almost removed from their population from years of trench warfare across the Western Front. The United States left the comfort of neutrality and entered the world’s stage in the final act of the war and setting it up as a world power. Public Relations as a professional occupation, plasma for blood transfusions, wrist watches, trench coats, and most modern music in general; all conveniences or common concepts of today that we likely forget where they came from.

That’s where the World War One Centennial Commission comes in, and specifically its Chief of Staff Dale Archer (Central Oklahoma). As a congressionally chartered organization, the World War One Centennial Commission focuses on three fundamental objectives: Honor, Commemorate, and Educate.

Their efforts have been in the works for over ten years. Their largest project, a national memorial in Washington, D.C., is coming closer into view every day. But it’s not without its own unique elements.

“I don’t have a constituency to advocate for,” Archer shares. “Corporal Frank Bucklers (ret.) was the last American veteran who passed away in 2011. So, I focus instead on the children and grand-children of the WWI generation. They’re the ones carrying those memories and that vision.”

They already have a future home picked out that’s fitting for its namesake and its location. With plans to be placed in Pershing Park (named after General John Pershing), the memorial will be right next to the White House and within the same neighborhood as the National Mall that plays host to many other memorials to previous conflicts.

“There’s no rule book or study guide about how to design and build a memorial in Washington, D.C. because every conflict is different, and every constituency is different,” says Archer. “We’ve also built all of our memorials in reverse chronological order, which is unique.”

The reverse order of the memorials means securing funding from American veterans of WWI in the last decade has been improbable and since Buckles’ death, impossible. This is a critical component of the memorial project because all funding has to be secured privately. For an idea of the cost of such a project, the much larger World War II memorial raised a total of $197 million.

But for Archer, the project’s importance as a tool to honor and educate is a critical element.

“Let’s look at the Meuse-Argonne offensive by itself. It’s one of the final major offensives of the war and is the deadliest battle in American history with over 26,000 killed in action. In a short period of time, 26,000 sons, brothers, and fathers are gone. And those who lived came back with both physical and mental injuries themselves. They called it shell-shock and we know it today as PTSD. For some perspective, over 4 million American personnel were mobilized during the war. That’s some perspective on how much this impacted and affected American society.”

If the facts sound shocking because you’ve never heard them before, then you’re likely not alone which is why the memorial’s return value for American society is priceless in Archer’s opinion.

“If we continue to forget people that served us in the past, we’ll continue to forget people who serve us in the present and future.”

And he makes an astute point. We hear about Normandy, Okinawa, the Tet Offensive, and Gettysburg but how often do we hear about the Meuse-Argonne? It’s a sobering reflection for a nation that prides itself on honoring its veterans and the sacrifices of its citizens in the name of liberty.

“If you were in college you would have been drafted. If you were able-bodied you would have been drafted. This was before the concept of deferments. The baseball season was even shortened because it was deemed that professional players could be drafted. Those were the sacrifices that people made.”

Archer, a founding father of the Mu Tau (Central Oklahoma) Chapter, also has significant personal attachment to this project.

“My father was a Korean War veteran. Knowing my own family’s military history, the Fraternity’s military history, and then recognizing there was an entire generation of forgotten veterans from a war 100 years ago means I need to do whatever I can to make sure people are not forgotten, particularly those that died so that we can enjoy our freedoms today.”

Archer encourages not just Sigma Nus, but every American to get involved in some way with the efforts to build the memorial in Washington, D.C. He suggests that individuals can do things as small as contributing $1-3 towards the memorial or even downloading the “Bells for Peace” phone app that will prompt you to chime your own bells 21 times at 11 a.m. on November 11, 2018 in honor and commemoration of WWI’s Centennial.

Whether it’s through a donation or bell ringing, Archer points out the purpose behind it all through the lens of his own Sigma Nu experience.

“To govern each act by a high sense of honor has been a thoughtful and meaningful practice for myself every second, minute, hour, and day. Am I bringing honor to the mission I’m serving? Am I honoring the people who’ve come before me? Am I honoring the person right in front of me today? It really helps us focus on what’s important and how to navigate life.”