Welcome to the resource library for Phase II participants. The following information provides a deeper dive into each of the topics from this phase.

What to Expect in Phase II

As you are well aware, Phase I focused on giving Candidates a foundation of knowledge regarding Sigma Nu, ethics, values, leadership, and teamwork. With this foundation, we believe Sigma Nu is giving Candidates the experiences and knowledge they need to be positive and productive members.

Phase II is designed to further the knowledge and experiences created in Phase I, but more specifically, Phase II is about improvement. As a participant of Phase II, you and your chapter will benefit through the growth of the collective voice of you and your fellow Phase II participants. An additional benefit to your participation in Phase II is that you and your participating brothers will begin to take further ownership of what is happening in the chapter.

Phase II is focused on giving you the skills and experiences you need to be more of a contributing member in the chapter and the skills to be successful in your roles in organizations on campus and in the chapter. You will also find that the skills you take away in Phase II will serve you well after graduation. Put simply, Phase II focuses on building a better brotherhood and the result is a better Sigma Nu experience for you and your chapter.

Explaining Phase II

Phase II is made up of the following sessions:

- Seven Habits of Highly Effective People

- The Leadership Challenge

- Visionary Leadership

- Effective Change

- Myers-Briggs

- Teams and Decision Making

- Controversy with Civility

- Living Our Values

Click here for full session descriptions.

Within each session, there are additional features that will help you get the most from your experience with Phase II:

- Reflection Questions – questions at the end of session that the LEAD Chairman may assign to help you process and better understand what you are learning.

- Application Ideas –ideas you can use to apply the information that you learned in each of the respective Phase II sessions. By taking time to use the Application Idea after each session, you will reinforce what you’ve learned by applying the concepts from the session to a “real world” scenario. Ask your LEAD Chairman or the session facilitator to share the application ideas at the end of each session.

- Leadership Development Plan – This plan will help you focus on how you can improve as a leader and help you assess your strategies and weaknesses.

A Word from the High Council

Before you close out of this orientation session, take a moment to review the following note from the High Council of Sigma Nu Fraternity. By doing so, you will understand the importance, and support, or the LEAD program by the elected leaders of our organization.

Dear Member of Sigma Nu:

We welcome you with enthusiasm to the program that will guide Sigma Nu into the future through the most significant undertaking in the fields of leadership and ethics of any college fraternity. We are grateful for your commitment to the LEAD Program. The High Council and the Educational Foundation Board of Directors are in total support of your participation.

Sigma Nu’s LEAD Program stands for: Leadership, Ethics, Achievement, and Development.

Sigma Nu believes that the development of ethical leadership is a valid expectation for higher education and that no entity on the college camps is better suited to address this issue than the unique social fraternity system that exists in this society.

Destined to become the hallmark of ethical leadership development at the colleges and universities which host a Sigma Nu chapter, the LEAD Program was launched at the 1988 Grand Chapter in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Grounded on a conviction that our society must regain the ethical standards on which it was built, and that Sigma Nu’s heritage of Love, Honor, and Truth provides a solid base for these standards, this fraternity has committed its leadership and resources to the achievement of the following objective:

To provide a quality leadership development program designed to foster ethical leadership and a high sense of honor among our collegiate brothers; and, to encourage future ethical leadership in government, business, academia, and community.

As a participant in the LEAD Program, you will be an important link along with a nucleus of alumni and collegiate brothers to provide the moral, mental and motivational energy to make it happen. We have every confidence that you will do just that.

Fraternally,

High Council, Sigma Nu Fraternity, Inc.

Directors, Sigma Nu Educational Foundation, Inc.

Wrap Up

It’s our hope that this into has given you an idea of what you can expect during your participation in Phase II; however, if you find yourself feeling unsure, or that you don’t understand why a topic has been included in this phase, we ask that you trust the process. Phase II has been put together specifically to help you, and your chapter, to improve and the sessions of Phase II will do just that, if you trust the process.

Reflection Questions & Application Ideas

Reflection Questions:

- What do you hope to get out of your Phase II experience?

- How can you make the most of your Phase II experience to positively impact yourself and your chapter?

Application Ideas:

- Begin work on your Personal Leadership Development Plan. Complete your plan before you finish Phase II. Review the plan and your progress relative to achieving what you set out to do.

- Identify a leader in the chapter and on campus that could serve as a role model or mentor. Ask this individual to assist you in your development as a leader.

Introduction

This session is derived from the book The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen R. Covey. This session will help you establish an understanding of the underlaying habits that will positively affect your leadership style.

Leadership as a Habit

As you will recall from Phase I, Session 8: Leadership – The Basics, there are two major schools of thought regarding leadership. The traditional paradigm is a top-down, management-oriented design of leadership that is focused on power and control. The emerging paradigm, however, is a multi-directional, team-oriented design that focuses on pursuing mutual purposes that intend real, significant change. This emerging paradigm is focused on doing something, not just holding a position. It is this emerging paradigm that Sigma Nu has adopted as its foundation for the concept of leadership.

The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People is a direct fit to this emerging leadership paradigm and Sigma Nu’s concept of leadership, because these habits are action-oriented. These habits encourage leaders to be forward thinking and to always consider what is best for the group, not just themselves. By understanding, accepting, and utilizing these habits in your daily role as a leader in your chapter you can, and will, become a more effective leader. The skills and traits you can take away from this session will serve you not only during your time in the chapter, but after graduation as well.

Explaining Effectiveness

Take a moment and think about the traits you would use to describe an effective person.

Now consider the traits you would use to describe an ineffective person.

One of the keys to be successful is maintaining a good balance in your life.

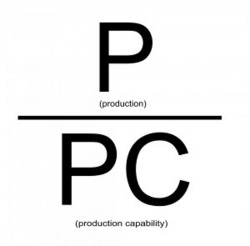

Effectiveness: The Goose and the Golden Egg

The P/PC balance concept can be easily understood by remembering Aesop’s fable of the Goose and the Golden Egg. It may seem a bit childish to include fables in a discussion about leadership habits but be openminded as we review a short version of this story.

This fable is the story of a poor farmer who one day discovers in the nest of his pet goose a glittering golden egg. At first, he thinks it must be some kind of trick. But, as he starts to throw the egg aside, he has second thoughts and takes it to be appraised instead.

The egg is pure gold! The farmer can’t believe his good fortune. He becomes ever more incredulous the following day when the experience is repeated. Day after day he awakens to rush to the nest and find another golden egg. He becomes fabulously wealthy; it all seems too good to be true.

With the farmer’s increasing wealth, though, comes greed and impatience. Unable to wait day after day for the golden eggs, the farmer decides he will kill the goose and get all of the golden eggs at once. When he opens the goose, though, he finds it empty. There are no golden eggs and, now, there is no way to get more. The farmer has destroyed the goose that had produced them and his wealth.

This fable addresses the principle of natural law; the basic definition of effectiveness. Most people see effectiveness from the golden egg paradigm: the more you produce, the more you do, the more effective you are.

But, as the story shows, true effectiveness is a function of two things:

- What is produced (the golden eggs); and,

- The producing asset, or the capacity to produce (the goose).

If you adopt a pattern in life that focuses on “golden eggs” and neglects the “goose,” you will soon be without the asset that produces “golden eggs.”

This fable accurately describes the parts that make up the concept of P/PC balance. In this formula, P/PC, P is the production of desired results, PC is the production capability. The challenge is that most people see effectiveness from the golden egg paradigm (the more you do, the more you’ll produce). However, this is not necessarily the case as it often leads to burnout and loss of interest in things that are enjoyable. There must be an acceptable balance in every situation.

Habits

As the title indicates, there are seven habits that are addressed in this session:

- Be Productive

- Begin with the End in Mind

- Put First Things First

- Think Win/Win

- Seek First to Understand, Then to be Understood

- Synergize

- Sharpen the Saw

Defining Habits

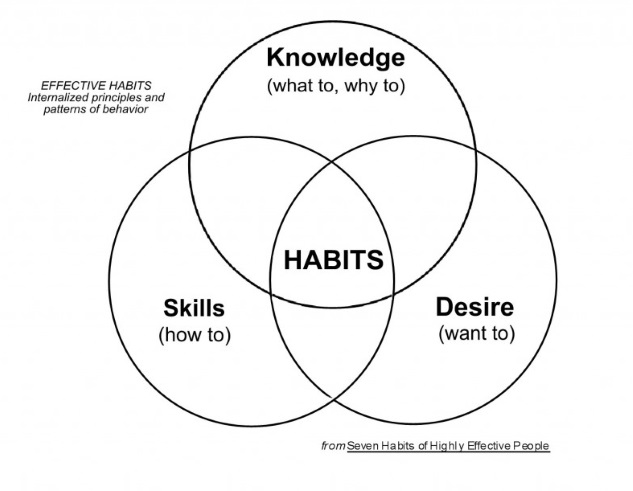

So, let’s begin with a definition. What is a habit? Stephen Covey defines a habit as “the interaction of knowledge, skill, and desire.”

The key to the Seven Habits, as stated previously, is balance. Balance doesn’t happen overnight; it is something you must use daily to be effective. This brings us to the first of the seven habits, Be Proactive.

Habit 1: Be Proactive

The difference between people who exercise initiative and those who don’t is night and day. It takes initiative to create the P/PC balance of effectiveness in your life. As you review the other six habits, you’ll see that they all depend on the development of your proactive muscles. Each of the other six habits puts the responsibility on you to act. If you wait to be acted upon you will indeed be acted upon.

No one likes to feel forced to do something, especially if we feel as if we don’t have a choice in the matter. That’s why it is important to realize what drives proactivity. Proactivity is driven by values, whereas reactivity is driven by feelings, emotions, and circumstances.

Take a moment and consider three things that you could do on a daily, or weekly, basis that would make you more proactive – as a student, fraternity member, or person.

Habit 2: Beginning with the End in Mind

The next habit is “Begin with the End in Mind.” To illustrate what is meant by “Begin with the End in Mind”, consider the following story.

In your mind’s eye, see yourself going to the funeral of a loved one. Picture yourself driving to the funeral parlor, parking the car, getting out, and walking to the front door. As you walk inside the building, you notice the flowers and the soft organ music. You can see the faces of friends and family you pass along the way. You feel the shared sorrow of loss, and the joy of having known, that radiates from the hearts of the people there.

As you walk down to the front of the room and look inside the casket, you suddenly come face-to-face with yourself.

This is your funeral, three years from today.

All these people have come to honor you, to express feelings of love and appreciation for your life. As you take a seat and wait for the services to begin, you look at the program in your hand. There are to be four speakers. The first is from your family, immediate and also extended – brothers, sisters, nephews, nieces, aunts, uncles, cousins and grandparents – who have come from all over the country to attend. The second speaker is one of your friends, someone who can give a sense of what you were as a person. The third speaker is from the fraternity. And the fourth is from your church or some community organization where you’ve been involved.

Habit 3: Putting First Things First

Habit three is “Put First Things First.” Take a moment and just think about what this means.

Successful people have a habit of doing things that failures don’t like to do. These successful people don’t necessarily like doing these things either, but their strength of purpose drives them to get things done. So, let’s consider what successful people are doing that aids them in being successful.

In “Putting First Things First”, you are dealing with many of the broad perspective questions that arise in everyday life, but more specifically you are dealing with issues like time management and prioritization. Ultimately, these issues can be categorized as personal management.

Personal management has progressed through four evolutions over time.

- The first generation was characterized by notes and checklists reflective of the present; that is, “What do I need to do today?”

- The second generation took a further step and began looking to the future. This evolution was characterized by calendars and appointment books; an attempt to look ahead to schedule events and activities in the future.

- The third generation began to establish priorities. As schedules and to-do lists continued to grow, it became crucial that we be able to determine what activities and tasks were the most important. This prioritization began to establish a sense of direction, not only to what needs to be done today but, also, to what needs to be done “tomorrow.”

- The fourth generation of personal management focuses on preserving and enhancing relationships and accomplishing results, not just things and time.

As personal management has continued to evolve, a new form of prioritization has emerged. This method of prioritization is based on the urgency and/or importance of a task.

Urgent factors are those that require immediate attention. These urgent factors are things that act upon us. Ringing phones, a crying baby or someone tapping you on the shoulder are examples of things acting upon us and are perceived as urgent. Urgent matters are usually visible.

Importance, on the other hand, has to do with results. If something is important, it contributes to your mission, your values, and your high priority goals. We react to urgent matters. Important matters that are not urgent require more initiative and more proactivity. We must act to seize opportunity, and to make things happen.

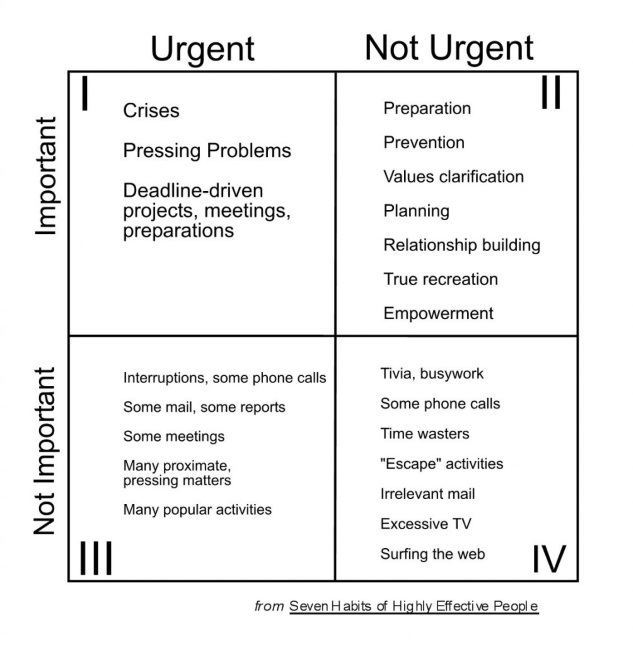

Look, for a moment, at the four quadrants in the time management diagram. Quadrant 1 is both urgent and important. It deals with significant results that require immediate attention. We usually call the activities in Quadrant 1 “crises” or “problems.” We all have some Quadrant 1 activities in our lives, but Quadrant 1 consumes many people.

There are other people who spend a great deal of time in “urgent but not important” Quadrant 3. They spend most of their time reacting to things that are urgent, assuming they are also important. The reality, though, is that the urgency of these items is often based on priorities and expectations of others. Quadrant 4 is “not important and not urgent.” This is the area that many students get stuck in because these include fun activities such as surfing the web, playing video games, and other time wasters.

Effective people stay out of Quadrants 3 and 4 because, urgent or not, they are not important. They also shrink Quadrant 1 down to size by spending more time in Quadrant 2. Quadrant 2 is the heart of effective personal management. It deals with things that are not urgent but that are important. It deals with things like building relationships, writing a personal mission statement, exercising, long-range planning, preparation – all those things we know we need to do, but somehow don’t do as often as we should.

Putting First Things First is the basis of relationships. To be truly effective in your relationships, you need to understand your roles in life.

Habit 4: Think Win/Win

Do you believe that you and your fraternity brothers should try to work together to find the best solutions when you have conflicts or disagreements? Why is it that when people have opposing views they are more interested in getting their own way?

The fourth habit is Think Win/Win.

- Win/Win is a state of mind and heart that constantly seeks mutual benefit in all human interactions.

- Win/Win means that agreements or solutions are mutually beneficial, and mutually satisfying.

- With a Win/Win solution, all those involved feel good about the decision and feel committed to the action plan.

- Win/Win sees life as a cooperative, not a competitive arena.

Many times, when dealing with issues in the chapter, members are thinking win/lose and are not being open to coming up with a solution that everyone can live with. By adopting this win/win mindset, you can build better relationships and a more open environment in groups you belong to, such as the chapter.

Habit 5: Seek First to Understand, Then to be Understood

Communication is one of the most important skills in life, if not the most important. We spend most of our waking hours communicating. But, consider this: You’ve spent years learning how to read and write, and years learning how to speak, but what about listening? What training or education have you had that enables you to listen so that you really, deeply understand another human being from that individual’s own frame of reference?

“Seek First to Understand” involves a very deep shift in paradigm. We typically seek first to be understood. Most people do not listen with the intent to understand; they listen with the intent to reply. They’re either speaking or preparing to speak. They’re filtering everything through their own paradigm and reading their autobiography into other people’s lives.

When another person speaks, we’re usually “listening” at one of four levels.

- We may be ignoring the other person, not really listening at all.

- We may be practicing pretending to listen, “Yeah. Uh-huh. Right.”

- We might also be practicing selective listening, hearing only certain parts of the conversation.

- Or, we may even practice attentive listening, paying attention and focusing energy on the words that are being said.

Very few of us, though, ever practice the fifth level, the highest form of listening – empathic listening.

Empathic listening means listening with the intent to understand; seeking first to understand, to really understand. Empathic listening gets inside another person’s frame of reference. You see the world the way they see the world, you understand their paradigm and how they feel.

You can start practicing this habit now. The next time you communicate with anyone, put aside your own intentions and seek to understand. When we understand each other, we create opportunities for creative solutions and alternatives.

Habit 6: Synergize

Synergy is the essence of principle-centered leadership. It catalyzes, unifies, and unleashes the greatest powers within people. All the habits that have been covered prepare us to create synergy in the chapter.

This sounds great, but you might be asking the question, “What is synergy?” Simply defined, synergy means that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. It means that the relationship which the parts have to each other is a part in and of itself. Sometimes this is described as 1+1=3 – the act of adding two pieces together, and how they interact, actually makes up a third part, meaning that when together they are more powerful than separate.

Synergy is everywhere in nature. If you plant two plants close together, the roots commingle and improve the quality of the soil so that both plants will grow better than if they were separated.

The challenge is to apply the principles of creative cooperation, which we learn from nature, in our interactions as brothers and as students. Fraternity life provides many opportunities to observe synergy and to practice it. Groups that are truly functioning well experience synergy. This often has to do with everyone feeling involved and everyone contributing to the effort in some way.

Habit 7: Sharpen the Saw

The last habit is Sharpen the Saw.

Suppose you came upon a man in the woods working feverishly to saw down a tree.

“What are you doing?” you ask.

“Can’t you see?” comes the impatient reply. “I’m sawing down this tree.”

“You look exhausted!” you exclaim. “How long have you been at it?”

“Over five hours,” he replies, “and I’m beat! This is hard work.”

“Well, why don’t you take a break for a few minutes and sharpen that saw?” you inquire. “I’m sure it would go a lot faster.”

“I don’t have time to sharpen the saw,” the man says emphatically. “I’m too busy sawing!”

This habit is about taking the time to sharpen the saw. It surrounds the other habits on the Seven Habits paradigm because it is the habit that makes all the others possible. It is the renewal of the four dimensions of yourself. If you don’t take time to pause, rest, and renew yourself as a student, brother, or officer, you will not be as effective as you could be.

The four dimensions of self that sharpening the saw renews are: Physical, Spiritual, Mental/Academic, Social/Emotional. Examples of each include, but are not limited to:

- Physical – working out, running, eating well;

- Spiritual – reflection on life, religion;

- Mental/Academic – classes, reading, intellectual conversation;

- Social/Emotional – things you do to have fun.

Wrap Up

The habits of effective leadership, as described previously, are indicative of the emerging paradigm of leadership and are consistent with the definition of leadership espoused in Sigma Nu. As you continue to develop and refine your own skills, be conscious of your efforts to incorporate these habits into your leadership style. They will make a difference.

Introduction

This session is derived from the book The Leadership Challenge by James Kouzes and Barry Posner. This session will help you to establish an understanding of the five basic practices of exemplary leadership, thus helping you to better understand yourself as a leader.

The Leadership Challenge

Much like Phase II, Session 1: The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, this session remains consistent to the emerging paradigm of leadership. As you will recall from Phase I, Session 8: Leadership – The Basics, there are two major schools of thought regarding leadership. The traditional paradigm is a top-down, management-oriented design of leadership that focuses on power and control. The emerging paradigm, however, is a multi-directional, team-oriented design that focuses on pursuing mutual purposes that intend real, significant change. This new, emerging paradigm is focused on doing something, not just holding a position. It is this new paradigm that Sigma Nu has adopted as its foundation for the concept of leadership.

The Leadership Challenge is just what the title implies: a challenge to you to better understand the five practices that effective leadership incorporates and how you might further utilize these practices in your daily interactions with others as a leader. By understanding, accepting, and utilizing these practices in your leadership style you will become a more effective leader. The skills and traits you can take away from this session will serve you not only during your time in the chapter, but after graduation as well.

Leadership vs. Management

Many people make the mistake of confusing leadership and management as being the same, but this is not true.

John Kotter, a noted author, has stated that the difference between leadership and management is clear.

Further, management is defined as, “the act, manner, or practice of managing, handling, supervision, or control.”

In Sigma Nu, leadership is defined as, "an influence relationship among leaders and collaborators who intend real changes that reflect their mutual purposes."

Clearly, there is a distinct difference between leadership and management. As we move through the rest of this session, keep these differences in mind because they will be important in developing your understanding of the five practices of exemplary leadership.

Characteristics of Leadership

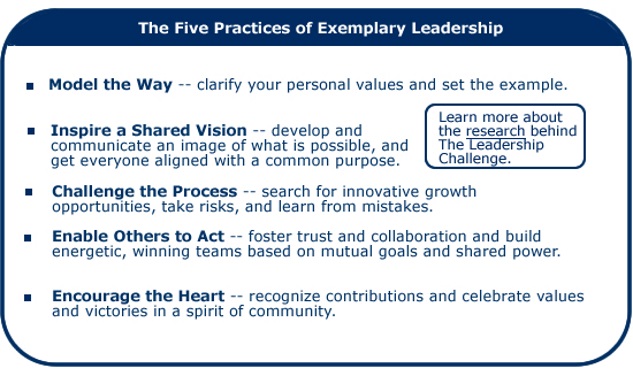

The five practices of exemplary leaders are: Challenging the Process, Inspiring a Shared Vision, Enabling Others to Act, Modeling the Way, and Encouraging the Heart.

Asking leaders about their personal best is only half of the story, though. It is important to note that leadership is a relationship between a leader and the members of the organization, just like Sigma Nu’s definition of leadership states: “…an influence relationship among leaders and collaborators…” The complete story can be seen only if we find out what others want from their leaders.

Take a moment and think about what characteristics you look for in leaders in the chapter.

To write The Leadership Challenge, the authors interviewed more than 1,500 managers from across the country. They asked them about the characteristics they looked for in a leader. The top four were:

- Honest – matching words with actions

- Competent – knows what they are doing

- Forward Looking – visionary

- Inspiring – enthusiastic about the organization

Think about the traits you look for in a leader in the chapter. How do they compare to the traits listed by Kouzes and Posner? Are they similar or different? If they are different, then why do you think they are different?

To better understand effective leadership, you must first consider your own experiences as a leader. Take a moment and think back to a time when you did your very best as a leader of other people.

- Consider that experience and what it was like for you, as a leader and a person.

- What are five to seven things you did that caused the experience to be your personal best.

- Wat would you say were the major lessons or morals about leadership that you learned from the experience.

The Five Practices

By studying the times when leaders performed at their personal best, Kouzes and Posner were able to identify the five practices common to most extraordinary leadership achievements. The five practices are:

- Challenging the Process

- Inspiring a Shared Vision

- Enabling Others to Act

- Modeling the Way

- Encouraging the Heart

Now that we know the five practices of exemplary leaders, let’s look into what they entail and how these practices can be developed and applied.

Challenging The Process

Challenge is the opportunity for greatness. Research has found that people do their best when there is the chance to change the way things are to the way things could be, should be, and/or the way they want them to be. Maintaining the status quo means accepting mediocrity, something that Sigma Nu does not accept.

Challenging the Process is exemplified by the following points…

- Leadership is most definitely an active process, not a passive process.

- While many leaders attribute their success to being in the right place at the right time, none of them sat still and waited for things to happen.

- Leaders who seek out opportunities for change and accept the challenges associated with change, test their abilities and are usually successful.

- Challenging the process means being a pioneer; being willing to step out into the unknown.

- To challenge the process, leaders must be willing to take risks, to innovate and experiment in order to find new and better ways of doing things.

- A leader’s primary contribution to the organization is the recognition of good ideas, the support of those ideas and the willingness to challenge the system to make changes happen.

- Leaders are learners; they are not afraid of making mistakes and they learn from theirs, as well as others’, mistakes.

Ideas for Challenging the Process

- Choose one routine task and do it as if it were the first time. Ask yourself fundamental questions – Why am I doing this? Why does it have to be done this way?

- Go on a field trip. Take a chapter member and go visit another Sigma Nu chapter. Find one thing that chapter does very well that your chapter could and should copy. Get it done.

- Find something that’s broken and fix it. “Is it your calculator, or is it your compensation system?”

- Find something that isn’t broken but should be. Break it.

- Encourage everyone to set up little experiments in their work. Start a “mad scientist of the week” award and give it to someone who made an interesting experiment (even a failed one) and who learned something.

- Take the next possible opportunity to tell everyone about the Worst Mistake You Ever Made and what you learned.

- Collect new ideas. Start an idea club. Ask everyone on the team to come in with one new idea to improve your work.

- Reward risk takers. Praise them. Give them little prizes. Give them the opportunity to talk about the experience and share the lessons. It’s money in the bank.

- Ask why. Next time you don’t understand a bylaw or procedure, make sure you get an explanation – or a change!

- Stand up for your beliefs, even if you’re a minority of one.

From The Leadership Challenge by Kouzes and Posner, Copyright 1987

Inspiring a Shared Vision

Once a leader identifies the areas that need to be changed, or that they want to change, they can decide where they want to take their organization.

It is the job of every leader to create a vision for their organization. Every great organization begins with a dream. The dream, or vision, is the force that invents the future. The more detailed, the richer and more descriptive the vision is, the greater the pull it will have on your chapter. Visionary leaders spend time thinking about the future and what it will be like when their organization reaches that next level of excellence.

Inspiring a Shared Vision includes…

- Vision is a desire to make something happen and change the way things are in an organization.

- When leaders and organizations create their visions, they create something that no one has ever created before.

- Taking time to think about vision; getting away. This is one of the best things you can do as a leader.

- Leaders inspire a shared vision by enabling others to see the possibilities that the future holds. They get people to buy into their dreams by showing how all will benefit from a common purpose.

- You cannot command commitment; you can only inspire it.

If you were asked what you want to accomplish this year, could you provide a descriptive answer? What if you were asked where you wanted to be in five years? While these questions are directed at your personal life, the concept of vision allows us to also apply them to organizations. If you haven’t thought about what you want your chapter to accomplish this year, or where you want it to be in five years, then you need to start thinking about it now.

Ideas for Inspiring a Shared Vision

- Develop a vision for today. Ask yourself, “Am I in the job to do something or am I in it for something to do?” Make a list of what you want to accomplish while you are in your current job – and why.

- Keep refining and updating your vision. Write an article about how you have made a difference. Date it for three years into the future. Be bold, imagine the best of yourself.

- Learn how to communicate your vision effectively. Take a course in effective presentations.

- Become a futurist. You are the “scout” for you group; you need a clear picture of what the future looks like. Make time each week to find out about future trends in your industry and your world. Join the World Futures Society. Read American Demographics or Omni magazine. Be informed and imaginative.

- Set time aside every week or talk about the future with your people. Make your vision of the future part of the staff meeting, a working lunch, and conversations by the water cooler.

- Listen – and learn. Ask your people what their dreams plans, goals are. Talk them over. Incorporate them into your group’s vision.

From The Leadership Challenge by Kouzes and Posner, Copyright 1987

Enabling Others to Act

As a leader, once you have decided what needs to change and where the organization is going, you need to focus on getting others involved and the teamwork that will be needed to accomplish these goals.

One of the most imperative responsibilities of any leader is to watch for potential in others and to help them act on their potential. Good leaders know they can’t do it alone. It takes good people working together to get extraordinary things done in organizations. There is a simple one-word test to determine if someone is on the way to becoming a leader: how often they use the word “we.” Leaders build teams with spirit and cohesion; teams that make people feel good about what they are doing. So, as a leader, when you identify a person with a lot of potential, you must encourage them to get involved and put them in a position to act on that potential.

Enabling Others to Act…

- Means making others feel like owners, not like working hands.

- Means involving others in planning and giving them discretion to make their own decisions.

- Means being considerate of the needs and interests of others.

- Means encouraging others to get involved and showing them how their involvement will make a difference.

- Requires an environment of trust and respect. You need to do everything you can to build respect in your chapter.

- Focuses on collaboration; getting people to work together.

- Makes others feel strong, capable and committed.

Ideas for Enabling Others to Act

- Always say “we.” It’s only a token of commitment to teamwork and sharing, but it will be noticed and valued.

- Create interactions. By bringing people together, you develop teamwork and trust. Bring a candidate along to the next meeting at one of the groups you belong to on campus. Schedule a lunch for two groups who don’t spend much time face-to-face.

- Keep people informed. Keep a public score card on your chapter. Post goals and monthly progress on the bulletin board.

- Ask brothers for their opinions and viewpoints. Share problems with them. That will demonstrate respect and trust.

- Involve people in planning. Next time you’re given a big project, call in all the people involved and plan together.

- Give people important work to do.

From The Leadership Challenge by Kouzes and Posner, Copyright 1987

Modeling the Way

Effective leaders are role models. As a leader and a member of your chapter, you have a responsibility to others to be the best Sigma Nu and best brother you can be. One way to do this is to stand up for your beliefs and practice what you preach. Being a role model doesn’t mean being perfect, but it does mean striving for excellence and to never settle for the status quo. Modeling the way means never asking someone to do something you are not willing to do yourself.

Modeling the Way can be exemplified in the following ways…

- Leaders know that while their position gives them authority, their actions earn them respect.

- It is consistency between words and actions that build a leader’s credibility.

- Values are at the core of this practice; they give direction to everyone in the organization.

- Look for teachable moments. Teachable moments are opportunities where you can highlight what is important as a Sigma Nu, leader, and human being. It is also a chance to teach a lesson.

- While officers may continually evaluate members and what they are doing for the chapter, members also are continually evaluating their officers. Their test: Does the officer practice what he preaches?

- Leaders who talk about their values can make a huge impact on members.

- Live Sigma Nu’s Cardinal Principles – Love, Honor, and Truth.

Ideas for Modeling the Way

- Do what you say you are going to do. Keep a notebook on hand. Write down your promises as you make them, and make sure you review them – and fulfill them – before you go home.

- Walk the halls; join a team. You can’t set an example working alone in your office with the door shut. Work with people.

- Publicize your “rules of the road.” Live by them. If top quality is your priority, don’t let a single flaw pass you by without comment and action – ever again.

- Talk with others about your values and beliefs. Put values on the agenda along with budget and schedules. Talk about them with reference to your next project. How does this project match your beliefs?

- Be expressive (even emotional) about your beliefs. If you’re proud of your people for living up to high performance standards, let them know. Then, go brag about it to others.

- Spend time on your most important priorities. Delegate, but don’t abdicate. Work with your team on the most important tasks.

- Pay attention to the little stuff, the small wins. Don’t wait until the big project is finished to celebrate. Have a party to celebrate finishing the project plan or the budget.

- Make people’s choices public and visible to others.

- Tell stories about people who are living their values in memorable ways.

From The Leadership Challenge by Kouzes and Posner, Copyright 1987

Encouraging the Heart

Encouraging the heart means to reward and recognize others. Getting great things done in an organization is hard work. It requires commitment, hard work, and persistence. Leaders must always encourage others in their work for the organization.

Encouraging the heart could be as simple as a handwritten thank you note, or as elaborate as a formal award ceremony. No matter how a leader chooses to recognize a member of their team, it is imperative that it be done with heartfelt sincerity. As a leader, you need to make a concerted effort to publicly praise deserving members of your chapter.

Encouraging the Heart…

- Leaders need to express pride in their members’ accomplishments.

- Make a point to tell others what people have accomplished.

- Make people feel like heroes.

- Reward those who are in challenging positions.

- Focus on each other on a day-to-day basis – take time to listen to each other.

- Let others know how much they mean to the organization.

- Find a way to celebrate accomplishments.

Ideas for Encouraging the Heart

- Link performance and reward together. Who does it fastest? With top quality? Who found a problem and solved it? Who represents fraternal values? Are those four people recognized? Is their performance rewarded? If not, why will they continue to give you their top performance?

- Reward extraordinary efforts. Don’t let them go by unnoticed or unpraised. People aren’t as willing to go all out when no one notices or comments.

- Make creative use of rewards. Make fun and imagination your bywords. Give a giant light bulb to the person who has the best idea of the month. Tailor ideas to your unique team.

- Say “thank you.” Write “You Made My Day” memos. Set a numerical target. Write 10 thank-you notes every week, praising people for jobs well done. If you can’t find 10 things to praise, look harder.

- Provide feedback about results. Feedback is critical. The sooner, the better. It can be a “well done” for meeting a target or a detailed debriefing session with a team about how the latest project went and what team members learned.

- Be personally involved. If you don’t’ attend chapter events, you’re sending a message that you are not interested.

- Be in love with what you are doing. Keep the magic alive.

From The Leadership Challenge by Kouzes and Posner, Copyright 1987

Wrap Up

As a leader and a Sigma Nu it is important that you focus on continuous improvement. There is always room for personal growth. Take time to reflect on your leadership knowledge and skills. By doing so you will become a better Sigma Nu, chapter brother, and leader.

The Nature of Vision

This session is designed to take you through a process of examining the concept of vision and applying that concept to your chapter.

In the past year, have you heard members in your chapter say, “everything is fine. We don’t need to change anything,” or something similar? Unfortunately, many people believe that the status quo is acceptable in organizations, but the status quo can tie down an organization to mediocrity. Is that what Sigma Nu is about – mediocrity? Building, or remaking a vision can jump-start the chapter and take it to the next level.

Visionary Leadership

Take a moment and think back to when you were seven years old. What did you want to be when you grew up?

What about the future? Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

- Where will you live?

- What kind of job will you have?

- What kind of relationships will you have?

- What will you be involved with in your free time?

If you have answers to any of these questions, then you have a pretty good idea of what vision is all about. Obviously, these were questions about your personal vision, but the same concept applies even more strongly to the idea of organizational vision and your role as a leader and member in your chapter.

Most people don’t take enough time to carefully think about, and reflect on, the future. Those who do, and base their strategies and actions on their visions, have a great opportunity to make a difference. This is why “vision” is so important to a chapter. A vision inspires others to action and helps shape the future. It does so through the powerful effect it has on the people in the organization. Vision uses images, language, and emotion to move an organization forward.

As Bert Nanus, author of the book Visionary Leadership, said, “There is no more powerful engine driving an organization towards long term excellence and success than an attractive, worthwhile, and achievable vision of the future.”

Vision Defined

Before going any further, it’s important that you understand what vision is and what it is not.

Vision is NOT…

- Feel good words. Many leaders who understand the powerful effects that the visioning process can have on an organization treat the visioning process as a public relations exercise. Yes, the images and language can play a useful role, but vision is also a practical tool for planning, priority setting, and assessment.

- A mission. To state that an organization has a mission is to state its purpose. Mission is a statement of core principles and answers the question “Why are we here?” Vision, on the other hand, imagines how that mission will be fulfilled in the future. It answers the question, “Where are we going?”

- Goals or strategic planning. Like visions, strategic plans offer a future state that is different from the current situation; however, unlike a vision, strategic plans offer a systematic, sequential strategy for getting to the future. This includes specific, quantifiable objectives.

Vision IS…

- The ideal state of the organization. This ideal state is what the organization will look like when it reaches the “next level.”

- An idea or image of a better, or more desirable, future for the organization. The right vision is an idea so energizing that it can jump-start the future and motivate members to use their time, energy, and the organization’s resources to make things happen. Vision always deals with the future and focuses on common dreams and values.

Characteristics of a Good Vision

A good vision includes specific characteristics. As a leader, it is important that you keep these in mind as you work with your chapter to establish the chapter’s vision.

Characteristics of a good vision…

- Realistic

- Idealistic – it is a stretch for the chapter

- Descriptive and rich in detail

- Appropriate for the organization and the times

- Establishes a standard of excellence

- Inspires enthusiasm and encourages commitment

- Easily understood and well-articulated

- Ambitious

The Core of Your Chapter

While the characteristics of a good vision indicate what must be considered in the formulation of a vision, an organizational vision must also be consistent with the values of the organization. The core of your chapter is the values and beliefs that guide it. In describing values, Love, Honor and Truth must be taken into account, but so should the additional values that your chapter finds important.

Defining values in the chapter is important because it shows that members are committed to those values. It also helps members hold each other accountable for living those values. Before you can decide where you are going as a chapter, you must clarify your values and what is important.

Take a few moments and complete the following sentence stems.

- A good member is one who…

- It is important that our chapter…

- The greatest legacy I can leave the chapter when I graduate is…

Taking Stock of Your Chapter

One of the first actions you should take is to assess your chapter – including the values and beliefs of the members. Knowing your chapter requires asking the right questions. You might be able to answer some of these questions by yourself, but more objective information is needed.

- What values and beliefs guide decision-making in this organization? Prevailing norms often determine attitudes towards the vision. These common beliefs offer two kinds of clues to leaders. First, areas of strong consensus are often visions waiting to be articulated. At the very least, they provide a strong foundation that leaders can use in building commitment. Second, the beliefs may point out areas of tension within an emerging vision.

- What are the chapter’s strengths and weaknesses? Visions are easier to fulfill if they can build on the chapter’s strengths.

- Does the chapter currently have a clearly stated vision? If so, what is it? If a vision already exists, the task changes – reviewing it and renewing a vision requires a somewhat different approach than creating a vision for the first time.

- What strategy is currently being followed to fulfill the current vision? Is it working? Useful visions provide guides to action by pointing out the discrepancy between what is and what ought to be. Just as physicians must understand the healthy body to make a diagnosis, leaders must base their decisions on what a successful chapter should be like. Some key questions here are: Has the chapter examined its current programs in light of the vision? What specific actions are being taken as a response to the vision? How is the new vision being supported by the members? Is progress toward the vision assessed at least twice a semester/quarter?

- If the chapter stays on the current path, where will it be headed in the next four years? Here is where leaders must apply their future vision, try to determine how the environment will change in the coming years and how the change will affect the chapter. The use of “What if…” statements will help here.

- Does the system (the chapter’s structures, policies, traditions and resources) support the current direction?

- Does the culture of the chapter support reflection, risk-taking, and collaboration? An effective vision requires that all members take a role in the organization. A chapter that encourages its members to work together through ad hoc and standing committees can create collaboration on a wide scale.

Adapted from Vision, Joseph Quigley, author

Co-Creating Vision

Step 1 – Complete the vision audit (from the facilitated workshop for this session) and vision worksheet with your Executive Committee.

Step 2 – Chapter Retreat: complete the vision worksheet and one or two additional exercises related to vision.

Step 3 – Begin to write your vision statement (newspaper article for your college/university newspaper).

Step 4 – Meet with group leaders to review and edit the vision statement.

Step 5 – Present a draft of the vision statement to chapter; do force field analysis (see item “C” below).

- Now that you have your vision and know what you want to do, you need to make sure that your vision can be successful.

- The organizational climate consists of the structures, processes and culture that collectively determine what the organization is and how it functions. The visionary leader must adapt the organizational climate to the new vision.

- One way to look at this situation is through a force field analysis. Here you want to: focus on forces that could keep the vision from being implemented; focus on forces that could help the vision become reality. There are three types of forces: Things that have to do with individuals; things that have to do with other people or groups; things of a non-personal nature, environment and cultural issues.

Step 6 – Begin strategic planning process; SWOT analysis.

- There is a complete Strategic Planning Retreat in All Chapter LEAD

- SWOT stands for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. To do a SWOT analysis, you should focus on what you believe are the key areas of the chapter (based on the Pursuit of Excellence Program and campus awards criteria).

- Once you have completed a SWOT analysis, you should begin to develop goals for each of the areas of the chapter.

- The goals should be specific, measurable, agreed-upon, realistic, and have a time constraint.

Challenges of Visionary Leaders

- They must “have” vision. That is, they must understand it well enough to tell if the chapter is headed in the right direction. The leader must resist the temptation to declare victory after the first few incremental changes.

- The leader must be deeply committed to the vision. Through time and energy, the leader must do whatever it takes to make the vision grow and succeed.

- The leader must be both directive and facilitative. Leading a chapter to develop and implement a new vision requires input, consensus, and cooperation, it doesn’t happen by itself. To be successful, the vision must be owned by everyone in the chapter. In addition, the leader must be willing to step aside and let others take on central roles in the process.

- The leader must be able to institutionalize the vision. No matter how much excitement is created in the initial steps of vision development, the vision will eventually wither and die unless the full resources of the chapter are behind it. Leaders must be able to make the necessary changes in structure, reallocate resources, and devise ways to continually assess programs.

- The leader must live vision in thought, word, and deed. Visionaries do not just communicate their dreams in so many words “they convey their stories by the kind of lives they themselves lead.”

Monitoring the Vision

- How well is the organization doing in moving in the desired direction? Are there enough changes being made, and is the rate of progress satisfactory?

- Are people committed to the vision, acting as if it were their own, and willing to take the initiative and incur risks to achieve the vision?

- Are the goals and priorities of officers – as well as of new projects and program ideas – consistent with the vision? Have new options opened up?

- Are the chapter’s structures, processes, plans, reward systems, and policies consistent with the vision?

- Do people feel they are pushing the boundaries of their field, that they are “where the action is”? Are they optimistic and enthusiastic about the prospects for the chapter?

- Are people communicating and cooperating with each other in the accomplishment of the vision, and are they being recognized for their participation in such activities?

- Are influential officers championing the vision and is there evidence of confidence in the leadership?

- Is the culture supportive of the vision or moving in that direction?

- Has the organization been innovative enough in implementing the vision?

The information required to answer these questions is available from many sources: direct observation and measurement, attentive listening, informal conversations and rap sessions, progress reports, plans and programs, task forces, and surveys, to mention just a few.

Tracking the Vision

- Do all external stakeholders in the organization – especially college/university administrators, parents, and alumni – understand and support the vision? Do they view it favorably?

- Is the vision accomplishing its purpose in terms of the organization’s measures of effectiveness? For example, are trends in membership numbers, scholarship, involvement, and reputation as expected within the new vision?

- How is the environment changing in ways significant for the organization’s sense of direction? Specifically, are there new threats or opportunities surfacing among other fraternities or potential members?

- How is the external environment changing in ways significant for the organization’s sense of direction? Specifically, are there new threats or opportunities surfacing in the social, economic, political, and technological environments that could affect the viability of the vision statement?

From Vision, Joseph Quigley, author

Consensus

To create some kind of consensus out of the opinions of your members, you must establish an arena where a dialogue can occur. A dialogue is a conversation that seeks to form a judgment based on mutual understanding rather than aggressive debate. People will still seek to persuade each other, but with the assumption that disagreement will lead to mutual learning and a more informed decision.

Preparing the Ground for Skillful Discussion

- Create a safe haven for participants. Because people from the entire chapter will be part of the process, the “turf” of the vision retreat must belong to no one. The symbols and trappings of power, prestige, and status should be minimized. As another power equalizer, all participants in a skillful discussion should expressly agree to “treat each other as brothers.” Curiosity, respect of and support for each other’s opinions and feeling are essential.

- Make openness and trust the rule rather than the exception. People must feel secure that they can speak freely, without fear of being the target of criticism, ridicule, or retribution. Thus, there must be a ground rule that people will not have their remarks attributed to them outside the room, unless they agree. Agreeing on a set of ground rules is only the beginning. Trust develops only if every participant continues to act in a trustworthy manner.

- Encourage and reward the injection of new perspectives. The exchange of perspectives and points of view, not the selling of them, is the issue.

How to Listen in Skillful Discussion (or any time)

- Stop talking: to others and to yourself. Learn to still the voice within. You can’t listen if you are talking.

- Imagine the other person’s viewpoint. Picture yourself in his position, doing his work, facing his problems, using his language, and having his values.

- Look, act, and be interested. Don’t doodle, shuffle or tap papers, or whisper to your neighbor while others are talking.

- Observe nonverbal behavior, like body language, to glean meanings beyond what is said to you.

- Don’t interrupt. Sit still past your tolerance level.

- Listen between the lines, for implicit meanings as well as explicit ones. Consider connotations as well as denotations. Note figures of speech. Instead of accepting a person’s remarks as the whole story, look for omissions – things left unsaid or unexplained, which should logically be present. Ask about these.

- Speak only affirmatively while listening. Resist the temptation to jump in with an evaluative, critical, or disparaging comment at the moment a remark is uttered. Confine yourself to constructive replies until the context has shifted, and criticism can be offered without blame.

- To ensure understanding, rephrase what the other person has just told you at key points in the conversation. Yes, I know this is the old “active listening” technique, but it works – and how often do you do it?

- Stop talking. This is the first and last, because all other techniques of listening depend on it. Take a vow of silence once in a while.

Emphasis on consensus. The most common mechanism for democratic decision-making is voting, which tends to be fair and efficient; however, voting also has some disadvantages.

- Participants may spend the discussion time counting heads rather than listening to viewpoints.

- Voting may lead to premature foreclosure; when participants face disagreement, they may be tempted to just vote no and move on, rather than exploring the issue in depth.

- Voting creates winners and losers; even when done fairly, the minority may feel as though their voices have been silenced.

From the Fifth Discipline Fieldbook

Wrap Up

For future success to be a probable reality, an organization must take the action of defining what that future success looks like. As a leader, you have the responsibility to assist your chapter in determining that vision. Understanding what a vision is and what it can do for your chapter is vital so that you and the chapter can utilize the visioning process effectively. The information and knowledge you have gained, and the further understanding you will garner form the facilitated session, is just the first step. From here you are challenged to take this concept to your entire chapter and together, work to create a vision for the chapter.

Change is Constant

There is no one perfect way to approach the change process. There is always a different method or strategy that could be used to get an effective, positive result. For leaders, the ability to take a different view, or the willingness to at least try to see things from a different paradigm is essential to the change process. By doing so, you can help your chapter implement change and create a culture of innovation

Take a moment and think about the changes that have occurred in the world just during your lifetime. Think about how different technology is today compared to when you were in elementary school (e.g. the iPhone didn’t exist until 2007!). Think about the types of jobs people are in today versus 50 years ago (e.g. there was no such thing as a computer programmer).

Change is constant. As people and organizations, we must focus on change because it is going to happen whether we want it to or not. If we don’t take the steps to be innovative and focus on continuous improvement, we won’t be successful in the long term.

Common Mistakes in Change Efforts

Take a moment and try to think about what percentage of traditional change efforts are successful? 80%? 60%? The answer is actually about 30%. Most people are shocked to hear that so few change efforts are successful. The problem, of course, is that most change efforts do not address all the components that they need to.

Some of the most common mistakes made regarding change are…

- Not creating a sense of urgency. People need to understand what is at stake if they are to move forward.

- Failing to create a powerful guiding coalition. Without a core group of people committed to the change effort, you are setting yourself up for failure.

- Underestimating the power of vision. Co-creating a vision for the organization is vital in getting people excited about the future. People support what they help to create.

- Not communicating the vision. If people in the organization do not understand the vision for the future and how it will look, it will be hard to persuade them to make changes.

- Permitting obstacles to block the new vision. New initiatives fail when members feel that change is not feasible. By eliminating obstacles, you help set yourself up for success.

- Failing to create short-term wins. By capitalizing on small successes that your organization is enjoying, you can build momentum and support for the change effort.

- Declaring victory too soon. A change effort is not complete until it is part of the culture of the organization. Care must be taken to continually emphasize the change and the benefits of the change initiative.

- Not anchoring the changes in the culture of the organization. If the change effort is to become part of “the way it’s done” in your organization, you need to take steps to highlight the new strategies.

From Leading Change by John Kotter

Real change focuses on changing the climate and culture of the organization and making continuous improvement a way of life. When chapter leaders bring ideas to the group, they help the members understand and accept ownership for the vision/change. This approach deals directly with people and their attitudes, which means it gets into the heart of organizations. It helps unlock creativity and promotes involvement and collaboration.

Understanding Change

Have you ever found your chapter to be going through a difficult time and a number of the members are justifying it through statements like, “It’s just a phase. We’ll be OK next year?” The only constant today is change. To be successful, organizations must work differently. If you hear people in your chapter settling for the status quo, then you and the other leaders have a responsibility to act on those warning signs. The need for innovation is not new, but the need for continuous change is. Let’s be clear about something though, “continuous change” does NOT mean change for the sake of change. Continuous change means constant improvement.

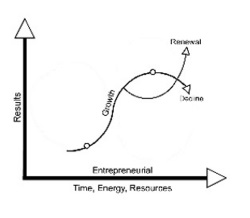

The Phases of Change

Every organization is in some stage of a development cycle. Some remain at a particular phase longer than others. Some do not survive. Some jump from one cycle to another. However, all organizations go through the same basic phases: infancy, growth, decline, and renewal. It is important not only to understand your chapter, where you are, and why you are there, but also to realize the decisions and actions that led to your current state. This will be valuable as you prepare for your next change initiative.

Look at the first curve. The curve demonstrates how all things start and how the growth cycle works. This growth cycle is the story of civilization, empires, sports teams, and businesses.

Let’s take a moment to understand the phases of change.

- Infancy: This phase is a time of innovation, invention, and a flow of new ideas. Members try to find what works and develop a good foundation for success. There is a lot of enthusiasm surrounding the organization during this time.

- Growth: This is the second phase of change and leads to expansion. The ideas that led to success are built upon. Chapters begin putting procedures in place so their success can be duplicated. Some characteristics of chapters in this phase include organizational success, focus on efficiency, effectiveness, and further development of systems.

- Decline: Late growth shows a breakdown in communication, rejection of innovation in favor of “tradition,” a lack of interest in taking risks, and low energy. Every growth cycle has a peak; therefore, if an organization remains locked on the curve, past the peak, it moves into decline. If we hold onto “what we have always done before,” the organization will end up in the decline phase.

The same ideas and practices that made the organization successful can begin to lead to its decline. Why? Doing the same thing, year after year, will not lead to the same results every year. If you remain on the growth curve past the peak – without making changes and implementing new ideas – you start the downward ride.

There is another option, though.

To break out of the box and move into an entirely new growth cycle and the renewal phase, an organization must “begin again.” To “begin again” means to rebuild. Renewal requires a conscious choice and it requires a renewal of not just the organization but the members in the organization.

- Renewal: This is a time when the members are making a conscious effort to understand what the organization is, revisit its purpose, core values, and focus on innovation and change.

The secret to constant growth is to start a new curve before the first one dies out. That is when you have the resources, time and energy to get the new curve moving.

Creating a Culture of Innovation

Webster’s Dictionary defines innovation as: 1) the introduction of something new, and; 2) a new idea, method or device.

For your chapter to excel, you need to begin to create a culture of innovation. Specifically, one that is change friendly. This is not a quick fix and will not happen overnight, but something that needs to be a constant effort. You should find a way to encourage innovative thinking to recognize new ideas.

In an earlier session, The Leadership Challenge, you reviewed the five practices of exemplary leadership and, more specifically, the practice of Challenging the Process. Challenging the Process means being aware of opportunities to question the status quo.

To apply that practice here, think of things in your chapter that fit the motto, “that’s the way we’ve always done it around here.” The list of things that come to mind should include things that frustrate you and things that you’ve always wondered why they were done that way. This might include traditions, rules, and how things are run or structured in the chapter.

Essentials to Effective change

The change process, as discussed previously, will not happen overnight. To help you enable change in your chapter, though, it is important that you understand the eight-step process to change developed by John Kotter.

- Establish a sense of urgency

- Create a guiding coalition

- Develop a vision and strategy

- Communicate the change vision

- Empower broad-based action

- Generate short-term wins

- Consolidate gains and produce more change

- Anchor new changes in the culture

Creating Major Change

Ways to Raise the Urgency Level

- Create a crisis by highlighting financial loss, exposing the chapter to major weaknesses compared to competitors, or allowing errors to blow up instead of being corrected at the last minute.

- Set targets so high that they can’t be reached by operating as usual.

- Stop measuring poor chapter performance based on narrow functional goals. Insist that more people be held accountable for broader measures of chapter performance.

- Highlight information about chapter performance to more members, especially information that demonstrates weaknesses compared to other fraternities on campus.

- Use your Leadership Consultant and advisors to initiate more honest discussion into Executive Committee and chapter meetings.

- Have honest discussions of the chapter’s challenges informally and formally. Stop “happy talk.”

- Bombard people with information on future opportunities, on the wonderful rewards for capitalizing on those opportunities, and on the chapter’s current inability to pursue those opportunities.

- Highlight progress from other fraternities your chapter views as competitors.

- Initiate benchmarking to discover how your chapter is doing in key areas compared to other Sigma Nu or campus fraternity chapters.

Creating a Guiding Coalition

Find the right people to work on the change initiative:

- With strong position power, broad expertise, and high credibility

- With leadership and management skills

Create Trust

- Through a carefully planned offsite retreat

- By communicating with all chapter members, informally and formally

Develop a Common Vision

- Sensible to the head

- Appealing to the heart

Developing a Vision and Strategy

Characteristics of an Effective Vision:

- Imaginable – conveys a picture of what the future will look like

- Desirable – appeals to the long-term interests of members, alumni, and others who have a stake in the chapter

- Feasible – the vision is a stretch for the chapter but is also realistic.

- Focused – the vision is clear enough to provide guidance in decision making.

- Flexible – the vision is general enough to allow individual initiative and alternatives in light of changing conditions

- Communicable – the vision is easy to communicate; can be successfully explained in a couple of minutes

Communicating the Change Vision

Chapter members need to know answers to the following questions:

- What will this mean to me?

- What will this mean to my brothers?

- What are the alternatives?

Key Elements in the Effective Communication of Vision:

- Simplicity – Members must understand the vision.

- Metaphor, Analogy & Example – A verbal picture is worth a thousand words.

- Multiple Forums – Big meetings and small, memos and newsletters, formal and informal interaction, all are effective for spreading the word.

- Repetition – Ideas sink in deeply only after they have been heard many times. Repetition is key.

- Leadership by Example – Respected brothers need to lead by example.

- Explanation of Seeming Inconsistencies – Find inconsistencies which undermine the credibility of all communication and fix them.

- Give-and-Take – Two-way communication is always more important than one-way communication. Create a dialogue with members.

Empowering Members for Broad-Based Action

- Remove structural barriers (traditions, policies, and rules) that hinder innovation and change in the chapter.

- Provide needed leadership training within the chapter (LEAD) as well as outside training through other campus organizations.

- Delegate and use committees effectively. This gives people ownership.

- As a chapter, set expectations for brothers. Make them clear, measurable, and concise.

Generating Short-Term Wins

Find things that are going well in the chapter and highlight them when possible. This helps build momentum and lets people feel good about what they are doing as members.

Characteristics of a short-term win:

- It’s visible…large numbers of people can see for themselves.

- It’s unambiguous; there can be little argument over the call.

- It’s clearly related to the change effort.

The Role of Short-Term Wins

- Provide evidence that sacrifices are worth it – wins greatly help justify the short-term costs involved.

- Reward change agents with a pat on the back – after a lot of hard work, positive feedback builds morale and motivation.

- Help fine-tune vision and strategies – short-term wins give the guiding coalition concrete data on the viability of their ideas.

- Undermine critics and self-serving members – clear improvements in performance make it difficult to block needed change.

- Keep opinion leaders (those members who are most respected) on board – provide opinion leaders with evidence that the transition is on track.

- Build momentum – turn neutrals into supporters and reluctant supporters into active helpers.

Consolidating Gains and Producing More

- Beware that the celebration of success does not replace the sense of urgency. Resistance is always waiting to reassert itself.

- More Change, NOT Less: The guiding coalition uses credibility afforded by short-term wins to tackle additional and bigger change efforts.

- Leadership from Executive Committee members: Executive Committee members focus on maintaining clarity of shared purpose for the overall effort and keeping urgency levels up.

- Project Management and Leadership from all members: The general membership both provide leadership for special projects and manage those projects.

- Reduction of Unnecessary Interdependencies: To make change easier in both the short and long term, identify unnecessary interdependencies and eliminate them.

Anchoring New Approaches in the Culture

- Culture refers to norms of behavior and shared values among a group of people.

- Norms of behavior are common or pervasive ways of acting that are found in a group and that persist because group members tend to behave in ways that teach these practices to new members, rewarding those who fit in and sanctioning those who do not.

- Shared values are important concerns and goals shared by most of the people in a group that tend to shape group behavior and that often persist over time when group membership changes.

When new practices made in a transformation effort are not compatible with the relevant cultures, they will always be subject to regression. Changes in a chapter can come undone, even after years of effort, because the new approaches haven’t been anchored firmly in group norms and values.

When new practices replace old in a chapter culture:

- They talked a great deal about the evidence showing how performance improvements were linked to new practices.

- They talked a great deal about where the old culture had come from, how it had served the chapter well, but why it was no longer helpful.

- They made doubly sure that new candidates knew the vision for the chapter and what would be expected of them as brothers.

- As a chapter, they tried hard not to promote anyone who did not appreciate the new practices and new vision.

- They made sure that any brothers being considered for Commander had none of the previous culture in their hearts.

From Kotter, John. Leading Change. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA, 1996

Organizing Change

Innovative thinking is a responsibility of every leader in your chapter, and that includes you. The benefit of thinking beyond today is the realization that you can create the future of the chapter. If you don’t influence the future of the chapter, then who will?

When you think about organizing the change effort, be strategic about who you enlist and approach others one at a time. Think about others who are respected in the chapter. Share your ideas with them. You will not need to convince everyone for a change to take hold.

As a leader, you are challenged to find areas, policies and traditions that don’t fit the mission of Sigma Nu and are not helping the chapter become the best it can be. Act today to start the change process.

Personality and Preference

If you know yourself well, then chances are you will be better able to relate to others. The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is the most widely used leadership personality indicator in the world. The data it provides allows not only for self-assessment of leadership style, but also provides for the analysis for interrelationships among work groups.

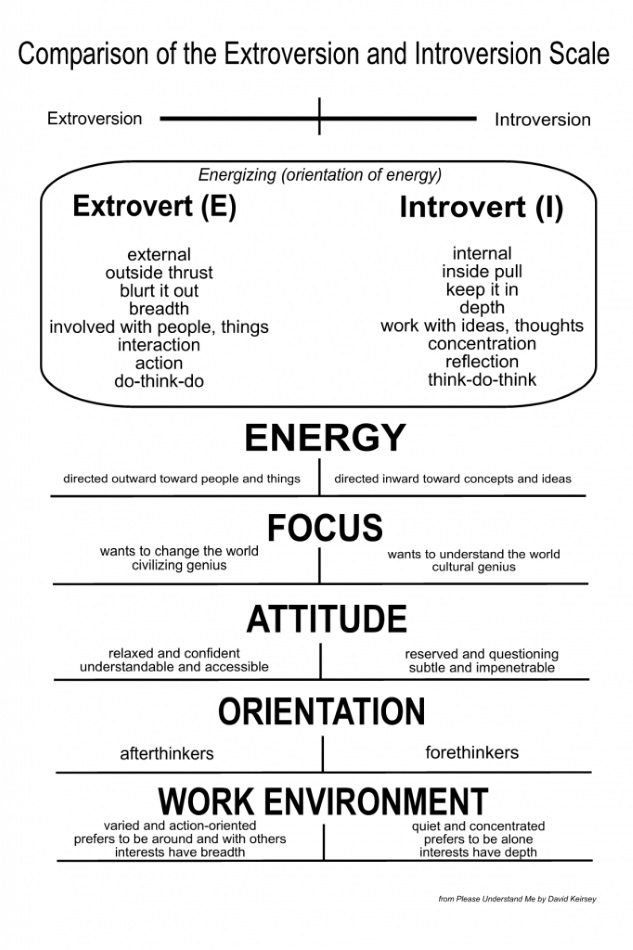

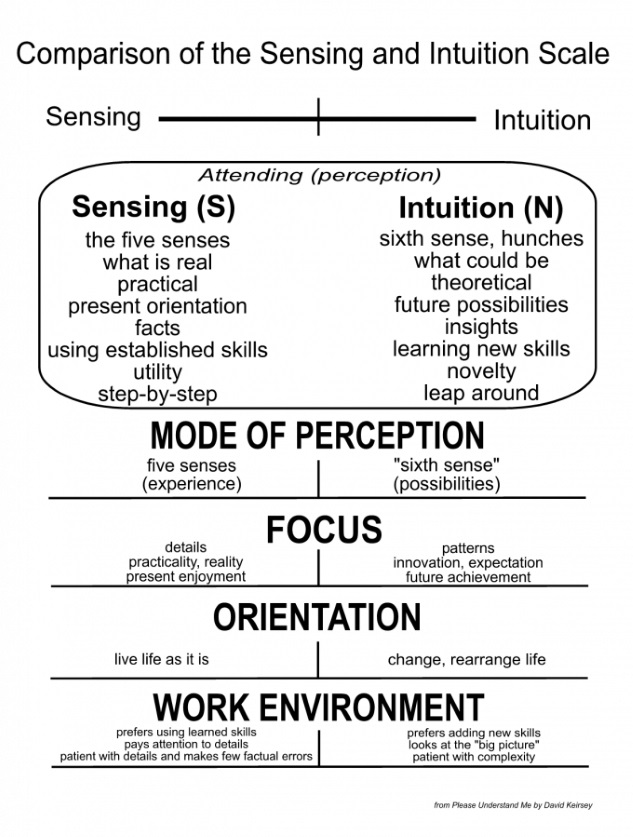

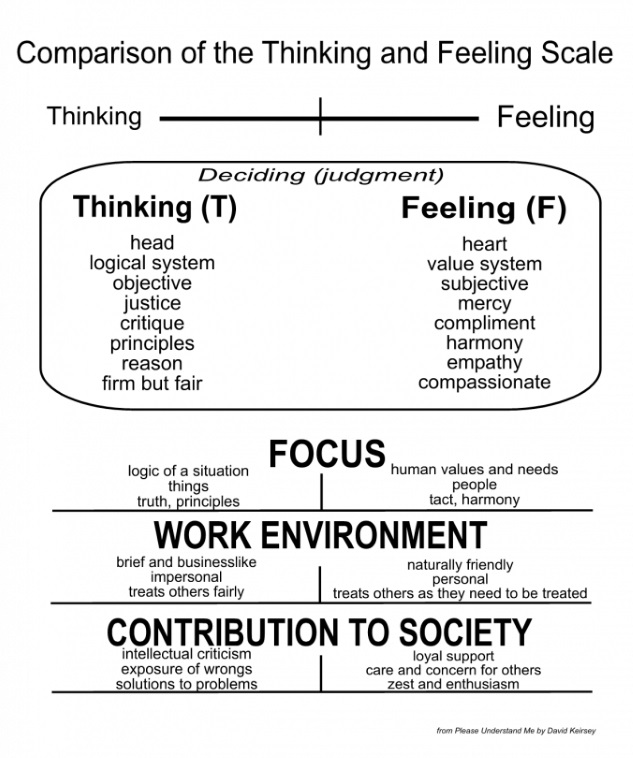

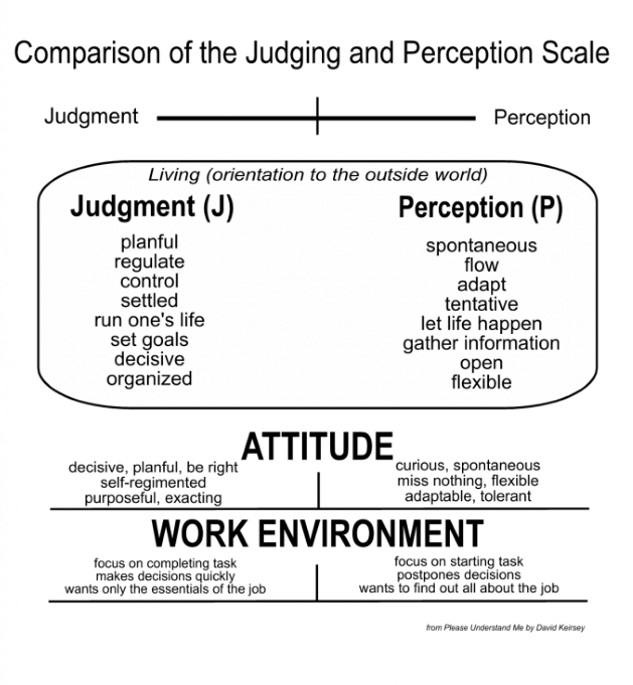

According to the theory, all of us have a natural preference for one of the two opposites on each of the four MBTI scales. You can use both preferences at different times, but not both at once and not, in most cases, with equal confidence. When you use your preferred methods, you are generally at your best and feel most competent, natural, and energetic. The MBTI indicates the differences in people that result from:

- Where they prefer to focus their attention (Extroversion or Introversion)

- The way they prefer to take in information (Sensing or Intuition)

- The way they prefer to make decisions (Thinking or Feeling)

- How they orient themselves to the external world – whether they primarily use a Judging process or Perceiving process in relating to the outer world.

As you use your preferences in each of these areas, you tend to develop behaviors and attitudes characteristic of other people with those preferences. There is no right or wrong to these preferences; they simply produce different kinds of people, interested in different things, drawn to different fields.

About the MBTI

The MBTI is a self-report questionnaire designed to make Carl Jung’s theory of psychological types understandable and useful in everyday life. MBTI results describe valuable differences between normal, healthy people – differences that can be the source of much misunderstanding and miscommunication. The MBTI helps to identify one’s strengths and unique gifts. You can use the information to better understand yourself, your motivations, your strengths and potential areas for growth. It will also help you to better understand and appreciate those who differ from you. Understanding MBTI type is self-affirming and enhances cooperation and productivity.

The authors, Katherine Briggs, and her daughter, Isabel Briggs Myers, were keen and disciplined observers of human personality differences. They studied and elaborated on the ideas of Carl Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist, and applied them to human interaction.

After more than 60 years of research and development, the current MBTI is the most widely used instrument for understanding normal personality differences.

Think about it this way, when you are dating someone, you want them to think about you and your needs, right? If you don’t pay attention to the personality type or preferences of someone, you are not allowing the best relationship to develop.

While the names of some of the MBTI preferences are similar in everyday use they have meanings that are different from their MBTI meanings.

- Extroversion does not mean “talkative”

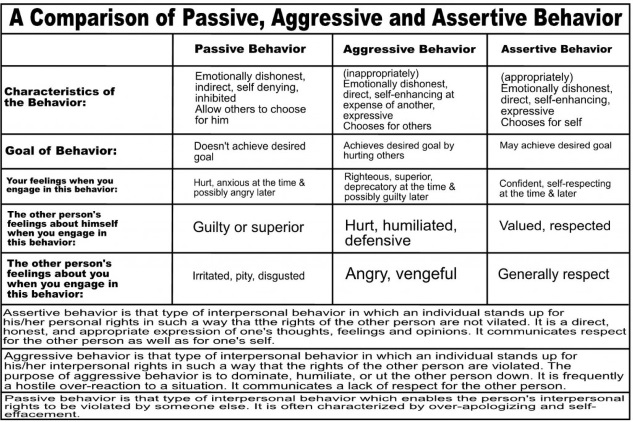

- Introvert does not mean “shy” or “inhibited”